Music and Story in The World

So let's hear some music! First I give a Tsarqan written by the Gnomic composer Tsuutam; then a typical countrydance from Auntimoany; third a piece of artmusic, which in the Eastlands is generally called Gnomic Music; and lastly, an orchstral excerpt from Zandam's Imperiall Garden Musicke. This last, the Imperial Garden Music is played by a large orchestra of many kinds of instruments. In the Eastlands, there are two basic kinds of orchestras, and the principal of them is the orchestra of sweet music. It is best suited for quieter, more modulated music, while the orchestra of strident music is more suited for outdoor festivals and raucous entertainments. Its loud reed and brass instruments rarely find their way into the serious music of the orchestra.

The typical art music orchestra in the Eastlands is mostly winds, and is typically heavy on sweet flutes (also known as blockflutes). The second largest group are the strings, comprised of ranks of lutes. This kind of orchestra is called the orchestra of sweet music on account of it comprising instruments that of softer sound that are capable of great dynamic flexibility. This classical orchestra developed from the consort music played by various Daine nations in the East, and so the instrumentation derives from what they favor. Other musical practices are also heavily influenced by the Daine, such as there being no keyboard instruments and very few instruments made from metal.

Members of the group sit generally upon cushions or low stools arranged comfortably on a rug strewn floor in a semicircle. At the front of the orchestra, are three circular wood framed lithophones. One has stone bars, another wooden bars and the third has bone bars, each chosen for their particular tonal coloration.

Behind them is the flute choir, consisting of as many as 40 instruments: eight each of great bass, bass and tenor and 16 trebles. They're arranged aesthetically with the trebles in the middle and the larger instruments around them and at the ends.

Behind the flutes are the stringed insturments. On the audience's left are two to four viols, and behind them, three zithers and one bass zither. Directly behind the flutes are the lutes: four archlutes (two on either side of the choir), eight principal lutes and eight octave lutes (arranged in front of the larger lutes and directly behind the flutes). Behind them are four hammered dulcimers and four harps. Some of the stringed instruments are strung in gut and others in bronze so there is a marked contrastof soft and loud. To give the bronze strung lutes something of a subdued tone, they can be fitted with soft dampers that take the edge off their tone.

On the left side of the orchestra are the reeds. Behind the great bass and bass flutes are eight chalumeaux: four trebles closest to the edge, then two tenors and two basses. Behind them are four treble cornameuses near the audience,then two tenors and two basses. Next to them are three racketts, two great bass and one tenor. Behind them are two treble, two bass oboes and one shawm. Sometimes the rackett players double on dulcians. These reeds and horns are not really all that loud. The shawm is the loudest instrument in the group, and for this reason, there is only one. The other reeds are fairly quiet and buzzy in nature.

On the right side of the orchestra are the horns. Immediately behind the bass and greatbass flutes are six olifants: two each of treble, tenor and bass. Behind them are three or four treble lisards and then two trumpets in the Daine style. Between them and the lutes are two or three bass horns, two bombardons and at the back a matched pair of two mammoth horns.

At the very back are the drums. On either side are the huge bass and tenor drums (like huge bodhrans); in the middle, three or four normal sized frame drums, iron cow bells, sistrums and a jingling crescent. Other assorted noisemakers may be called for, but these are typical.

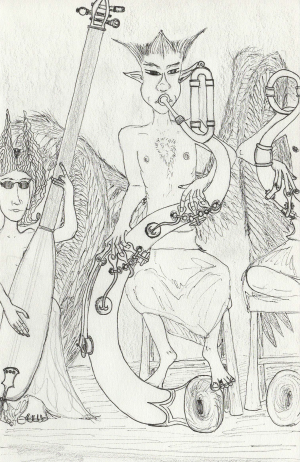

In the picture above, we can see on the left one of the archlutes, a long three-stringed bass boat lute type instrument and next to this the pair of grôtolifant, the big keyed bass horns made from curved sections of bronze tubing. Note that the olifants always come in "right" and "left" horns and each one is curved something like the tusks of the great olifants of the northern steppe.

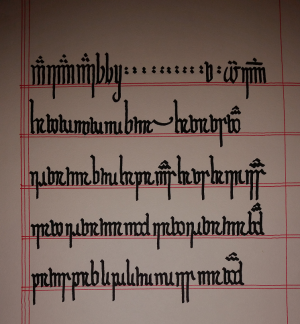

A note on musical notation: The system in most common use is that which was originally developped by the Teyor but has been continued and modified by the Daine of Auntimoany. The system is best suited to the simple vernacular music of the Daine, and indeed of all other peoples of the East) which is chiefly monophonic, though with excursions into the homophonic and heterophonic (as evidenced by the more courtly examples given above). Furthermore, it is designed with the simple system flutes and pipes favored by the Daine.

The system consists of compound glyphs that indicate pitch relative to the instrument as well as note duration (compare with solfege). Teyor and Daine music share microtonality as a fundamental, however, while Teyor music is fully quarter-step in nature, Daine music is primarily half-step in nature but with quarter & third step sensible pitches. The basic gamut runs SA, LI, NE, YO, RA, MI WE which denote the seven primary tonal steps of any mode or scale and relative to the true pitch of the instrument being played. (Thus, a cylindrical whistle of two feet sounding length will produce a c and thus is SA; a shorter or longer whistle's fundamental tone will also be called SA regardless of its true pitch.

Beyond the seven basic glyphs, four series of other glyphs indicate the high and low semitones of each tone (the sharps and flats that is to say) and also the rising and falling sensible tones. While the semitones are fixed in relationship to their basic tone, the sensible notes may vary between a quarter to a third of a step and are generally considered to be among the decorations of music rather than discrete tones. Some folks in more recent times have devised a system of diacritics that reside above or below the note glyph and that replace the numerous independent semitone and sensible note glyphs. These act much like accidentals in their modification of a given tone.

Four ranks of mensural glyphs indicate a tone's duration. Each rank roughly corresponds to one or more time signatures. While in this scheme crotchets and minims appear in multiple ranks, it can not be said that they are precisely equal in duration. The actual length of any note will depend upon the kind of tune, its mood, its tempo and the musical whim of the performer. Generally speaking, a crotchet that corresponds to the first or 3/8 & 6/8 rank will be quicker than a crotchet corresponding to the fourth or 4/4 & 2/2 rank.

Additional diacritics indicate phrasal borders, repeated sections, accents, register / octave to be played in and so forth.

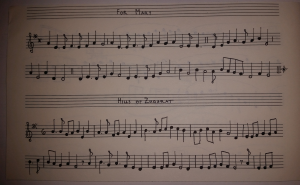

A radically different system of musical notation is coming into use for the more mensural music to be found in, for example, the court and concert hall. This music, based on the Gnomic, is much stricter in its application of meter and the older system of notation is rather inadequate to that task.

To the left we can see an image of a Daine melody, a lament, called Mereyelle. The usual convention of notating tunes is to first give the name of the tune and then the key pitch of the scale (in this case, LI or re) and then the mode the tune is to be played in (in this case Varant, which corresponds to the dorian mode).

Below that, we can see the same tune written in Western notation. Notice that unlike the tune Hills of Zugarat (another well known Daine tune and of which this is but the first half), which is a mensural tune, Mereyelle is nonmensural and thus has no time signature and no evenly divisible system of measures.

Let's listen to some Turghun music. This is a wedding dance of typical form. It is a slow air layed by a consort of notch-flutes. Typical of the genre, wedding dances are rather slow, almost melancholic pieces. There being no formal religious rites in a Turghun wedding, the newly mated couple simply announce their situation after which the families will arrange the feast. This kind of dance is played by the girl to accompany the guests and then her new mate to the place where the wedding festivities will take place. At times a single flute will play a theme, while at others a second flute in unison or several flutes in traditional intervals will play together the same theme.

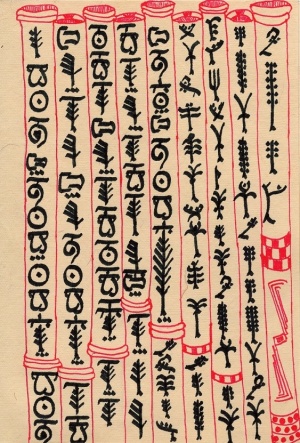

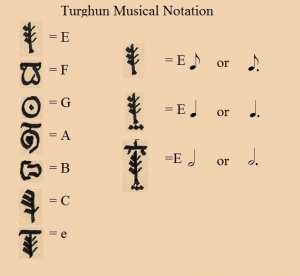

Turghun musical notation is read from top to bottom, left to right. Each symbol corresponds to a note played on the flute. Turghun flutes generally have five finger holes and one or more vent holes low down on the body of the flute. The usual mode or scale of their music is hexatonic. A flute whose five

finger note, its lowest note in other words, is E would have the scale E-F♯-G-A-B-C-e.

Apart from the six signs that represent each tone, there are diacritic marks that indicate an inspecific duration of time the note is to be played and also whether the tone is of the lower or higher diapason of the instrument. It is said that the duration is inspecific because the Turghun music is not strictly metrical in nature. They admit of three, or sometims four, basic lengths of notes. A short duration note is roughly equivalent to the quaver; a mid duration note is roughly equivalent to the crotchet or dotted crotchet; a long note is about the same length as a minim.

Certainly, this system of notation leaves much room for musical interpretation on the part of anyone playing from it. It is expected that any individual will play a given tune slightly differently and that a certain amount of variation will be introduced, in particular as regards rhythm, note duration and to an extent the use of subtle tuning changes on pivotal notes.

Turghun music is always monophonic in nature. If a second instrument or chorus plays the same music, there is never any harmonic component to the new music. The other instruments all play the same tune either in unison or at some interval. Listen to the notated example here.

The melodic instrument of choice is the flute, a bone or cane with sounding lengths of about 11 or 22 inches are most common. The tube is open at both ends and a notch is made at the proximal end where the airstream is blown causing the flute to sing. Flutes are made in many sizes and finger hole configurations, and makers will often craft a whole quire of instruments that play well together.

Storytelling is one of the most commonly practiced arts anywhere in The World. Every community, from the highest of the race of Teyor to the meanest hovels of Hotai, has someone among them who can spin an entertaining tale. But, as with all other arts and crafts, there those whose sole avocation and craft is the knowing and telling of stories. These professional storytellers rely much on the work of the Sawyers, those scholars and philosophers who collect and study stories from all over the world.

The term Sawyery refers to the study of the Old Stories, a set of disjointed but frequently crossculturally parallel or similar stories that tell of the most ancient of days. Typically, they relate to times before history was understood as an entity of its own and recorded for posterity, and thus describe the philosophical Golden Age. Typically, the Wise divide the Old Stories into various types depending upon their focus or intended character.

The philosophical study of the Old Stories is called sawyery and practitioners are called sawyers. Many are the collections of these stories that have been gathered in the libraries of the world. Fine examples can be seen at the great libraries in Alexandria of Kemeteia-Misser, Pretorias of Rumnias and Auntimoany as well. The sawyers' public trust is to preserve and expand collections of Old Stories; collect, collate and index the pronouncements and interpretations of philosophers, priests, and spiritual teachers; and to make available to the people whatever they wish to study from these collections. Therefore, anyone who can read or is accompanied by someone who can read is allowed unrestricted access to a library's collection of Old Stories. Several famous catalogues of Old Stories have been made by sawyers in recent centuries, especially those of Arny and Thompson, sawyers of Auntimoany who devised a topical and cross-referenced indexing system for their collection not only of stories but of the episodes and characters within them. Also well known is Franko Childer, a Husickite sawyer, who catalogued fables and various kinds of folk songs.

While ordinary story tellers rely on the diligent scholarship of the sawyers, they don't simply repeat stories verbatim. They retell, recombine, come up with wonderful new tales the like of which have never been heard before. Other storytellers keep closer to the old traditions conserved within the works of the sawyers. It is these granthund, or classical story tellers, like the fellow in the picture on the right, that bring the old myths and legends to life.

These granthund have memorised a great treasure trove of old story however, during more formal recitations, such as in the court of a gravio or in the emperor's Palas, it is usual for a large book of story to be placed upon a low stand for the granthund to refer to. By ancient tradition, story tellers always sit upon a low, comfortable stool and this is usually located upon a nicely woven rug, and they may only be served their food and drink upon earthenware vessels. This, they say, is a reminder to their own humility, for story should serve the good all folk of good will, and not serve the exaltation of the storyteller. Even so, some famous granthund are recorded in the annals of kingdoms and countryside inns, perhaps the best known of which Uthmanda, a nineteenth century granthund well known for his animated style and broad repertoire. It was said of him that he could hear a story of any length for the first time and ever after could retell the story without losing one single word or nuance of meaning.

Here is a typical tale told by the granthund of Auntimoany. It is from a well known collection of sawyery and is The Three Blind Mice.

On fornes waron thês thrêy blinden mês, ande market huw they dydetun omhemrene thês thrêy blinden mês! Nuw therh thon layne then under thon wayne ande on thon cutischen te bote! Ande twas thaar they sêhen en merveyelle thês thrêy blinden mês. For yn that cutiscen botwef Cgeolien cutiscete ande thaar ho wascqete ande duwemcraftihh was her cutiscend ande duwemcraftihh was her wascqend of botwef Cgeolien.

Nuw botwef Cgeolien was wifez te husbowend Sôlhaz se Mylwarthaz ande they buwetun om Yppsihdale. Ande nuw cwemand thôs thrêy blinden mês onhemrennend on thon cutiscen beouten they hemselfe stoppetun en wiscund brouwdeth beforon te this cat that hehôte Galgumel his scarpe clêyô! Nuw this Galgumel was en cyuwte, moscraftihh cats beouten with happe wase he under slepand; swo underhembehydetun thôz thrêy blinden mês yn thon pondarien under summe Rumeliardisce canaste. Ande twas fram that plâze they sêhen merveylles, they thrêy blinden mês.

For thas times yn cwâme botwef Cgeolien ombeberend thon tuwlgowecanife ande ombeberend thon hlavandmund yn her armes. For hwilam hit herselfe lîqete te hwessellen hwiles that ho west werkend; ande swo ho hwessellete this murih-morih tônde, thrêy swôyen hwat murnen of wenten ande douwthe. Ras-peh-bah — ras-peh-bah ho hwessellete ande — hwaq! — thonqete her canefez swo ho scrapete thon tuwlgowe. Ras-peh-bah — ras-peh-bah — hwaq! Ande hit mahhtylihh feyrete thêm mês, beouten senhhe Galgumel, he swefnete om delyciouso mês!

Cuwyckes ho liqete thon canefe ande omherwewôrthe te thon hlavandmund. For hwilam hit herselfe lîqete te hwessellen hwiles that ho west werkend; ande swo ho hwessellete this murih-morih tônde, thrêy swôyen hwat murnen of wenten ande douwthe. Ras-tam-car — ras-tam-car ho hwessellete ande — hwap! — ho clangete do se maytagges dorôn. Hit yngane te tansce ande senge — scuggabuubbascuggabuubba — ande theys mêsô wiscundum dydetun ouwtstande fram theys lêqes, ande they sêhen summe duwemmerglouwend! Ande hit mahhtylihh feyrete thêm mês, beouten senhhe Galgumel, he swefnete om bouwles of swete meluqe!

Ande la! se forne brâmaz yngane te tansce, suwôpend thêm thrêy blinde mês uwt fram thon pondarien ande thaar thêy sêhen merveyelles! For sange scuggabuubbascuggabuubba that maytagge, ande tanscete en braunwle that brâmaz ande adounfluhen allez thôz plattes thêz spênes yaan yâht wascqcalethes summe fethuwor miscgmaken stôqes te cgeoyne thon drauwgme with en forn trouwlez on touwe. Then spunwen they qerfund canifes te tansce yn thona êrem ofer thon murih drauwgme, hwessellend on rôndel theys murih-morih tônde, summe swôyen hwat murnen of wenten ande douwthe. Ras-peh-bah — ras-tam-car — ras-peh-bah — ras-tam-car.

And la! hwan that yerme Galgumel cunnete ande underhimbehyde under thon mense, se fornen brâmaz him suwatte te hys fundamund, ande he himselfe rane griend te therh thon yarden, ande besâhhtun yerme Galgumel they scarpe, morthenfulle qerfund canifes; ande befluhen they thrêy blinden mês uwt fram that cutiscen swo cwiqe swo mahtun . . .

Beouten la! he uwtgegange se tuwlgowecaniftez, hwa flêsce havet taxet, ande scêssete thôz yermen blinden mês, ande market nuw huw they doend omhemrene thês thrêy blinden mês! For he sengat this murih-morih tônde, summe swôyen hwat murnen on rôndel of wenten ande douwthe. Ras-peh-bah — ras-tam-car — ras-peh-bah — ras-tam-car.

- Thrêy blinden mês, thrêy blinden mês Botwef Cgeolien, botwef Cgeolien

- Mylwarth’ zande his murih wif’z

- Scrap’te thon tuwlgowe; liq’te thon ‘nîf

- Botwef Cgeolien, botwef Cgeolien

- Thrêy blinden mês, thrêy blinden mês!

In ancientry were these three blind mice, and see how they did run, those

three blind mice! Now, through the lane then under the wain and into the

kitchen to boot! And twas there they saw wonders, those three blind mice.

For in that kitchen goodwife Julienne cooked and there she washed and

magic was her cooking and magic was her washing of goodwife Julienne.

Now goodwife Julienne was wife to husband Sulcus the Miller and they lived in Yppsiy Dale. And now came those three blind mice running about into the kitchen but they themselves stopped a whisker breadth before to this cat that hight Gargamel his sharp claws! Now this Gargamel was a cute,

wisecrafty cat but with luck was he within sleeping; so away-them-hid those three blind mice in the pantry within some Rumnian basket. And twas from that place they saw wonders, those three blind mice.

For at that time in came goodwife Julienne on-carrying the tallowknife and on-carrying the wash in her

arms. For at times it her pleased to whistle while that she was working; and so she whistled this merry-mort tune, three soughing (notes) that mourned (recalled with melancholy) of winter and death. UT-SI-LA — UT-SI-LA she whistled and — whack! — thunked her knife as she scraped the suet. UT-SI-LA — UT-SI-LA — WHACK! And it greatly feared those mice, but old Gargamel, he dreamed of delicious mice!

Shortly she licked the knife and to-her-turned to the washing. For at times it her pleased to whistle while that she was working; and so she whistled this merry-mort tune, three soughing tones that mourned of winter and death. UT-RE-MI — UT-RE-MI she whistled and — whap! — she clanged-to the washer's door. It began to dance and sing — chuggabuubbachuggabuubba — and the mice's whiskers did out-stand from their bodies, and they saw this magic glow! And it greatly feared the mice, but old Gargamel, he dreamed of bowls of sweet milk!

And lo! the old broom began to dance, sweeping those three blind mice out

from the pantry and there they saw marvels! For sang chuggabuubbachuggabuubba the washer, and danced a brawl that broom and down flew all those plates these spoons yon eight washcloths and some four mismatched stockings to join the music with an old trowel in tow. Then spun the carving knives to dance in the airs over the merry music,

whistling in round their merry-mort tune, some soughing notes that mourned of winter and death. UT-SI-LA — UT-RE-MI — UT-SI-LA — UT-RE-MI.

And lo! when that poor Gargamel tried and under-him-hide under the table,

the old broom him swatted to his bum, and he him ran howling to through

the garden, and besought poor Gargamel the sharp, murdersome carving knives; and beflew the three blind mice out from that kitchen as quick as they could . . .

But lo! he out-went the suet-knife, who flesh has tasted, and chased those

poor blind mice, and mark now how they do run about, those three blind

mice! For he sings this merry-mort tune, some soughing notes that mourn in roundelay of winter and death. UT-SI-LA — UT-RE-MI — UT-SI-LA — UT-RE-MI.

- Three blind mice, three blind mice

- Goodwife Julienne, goodwife Julienne

- Miller and his merry wife

- Scraped the fat and licked the knife

- Goodwife Julienne, goodwife Julienne

- Three blind mice, three blind mice!