LIMBAWA ... Chapter 1

..... The sounds of Limbawa

The full range of sounds heard in Limbawa are given below according to the conventions of the I.P.A. (International Phonetic Alphabet)

| labial | labiodental | alveolar | postalveolar | palatal | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stops | p b | t d | k g | ʔ | |||

| fricatives | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | h | |||

| affricates | tʃ dʒ | ||||||

| nasals | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| liquids | r l | ||||||

| glides | w | y |

tʃ dʒ are the initial sounds of "Charlie" and "Jimmy" respectively. From this point on I will represent them by c and j.

ʔ represents a glottal stop (the sound a cockney would make when he drops the "tt" in bottle). In Limbawa this is a normal consonant ... just as real as "b" or "g" in English. From this point on I will represent it by @.

v is an allophone of f when inside a word and between two vowels.

z is an allophone of s when inside a word and between two voiced sounds.

ʃ is also an allophone of s when before the front vowel i or before the consonant y. ʃ is found in English and is usually represented by "sh" (as in "shell")

ʒ is an allophone of s when the above two conditions apply at the same time. ʒ turns up in English in one or two words. It is the middle consonant in the word "pleasure".

ŋ is an allophone of n when followed by k or g. ŋ is found in English and is usually represented by "ng" (as in "sing")

The basic vowels are a, e, i, o and u. Also the diphthongs ai, au, oi, eu, ia and ua are used. Note that while the sounds ia and ua are possible sound combinations in English, they each are realised as two syllables. In Limbawa the two components are more intertwined ... the flow into each other more. And they each represent only one syllable.

Two consonants can appear together at the beginning and middle of a word. The various combinations that are allowed at these two positions are stated later (see juzmi). Only two consonants are allowed word finally. These are n and s.

The vowels ia and ua can only occur in the final syllable of a word. If a suffix is added, making either ia or ua occur in a non-word-final syllable, then they must change to ya and wa respectively. However these changes can occur only in certain circumstances, depending on the consonant to the left of the y or w (refer to the table in the juzmia @aba section to see what combinations are acceptable). If the change to ya or wa is not allowed, then they both change to a simple a.

It has been reported that Limbawa stresses the second to last syllable in a word. However this is untrue. This report came about because Limbawa speakers pronounce the second to last syllable of AN UTTERANCE, louder. This lead some linguistic field workers who were elicitating single words from the Limbawa speakers, to draw the wrong conclusions.

Limbawa differentiates between words using tone. All single syllable words have either a high tone (for example pasᴴ = "I") or a low tone (for example paᴸ = me). All multi-syllable words lack tone (or can be said to have neutral tone). If a single syllable word, receives an affix making it into a multi-syllable word, then it will loose its tone.

I am representing the high tone with a full-stop sign after the syllable (in a similar manner the Limbawa writing system places a small dot to the right of a high tone syllable). If single syllable words are come across that are not followed by a full-stop, they can be taken as low-tone (as happens in the native Limbawa writing system).

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "allophone", "voiced sound" and "diphthong" are linguistic jargon. You don't have to worry if you don't understand what they mean.

.... some interjections

All languages have a small set of interjections. Usually they party fall outside the normal sound system rules. Limbawa is no exception.

iʃʃ ... an exclamation expressing sympathy (neutral tone)

xaa ... an exclamation of disgust (it starts of as a neutral tone, falls quickly then sort of lingers at a low level)...(the "x" represents the last sound in "loch")

aido ... an exclamation of frustration (rapidly rising tone on the "ai", a short break, then the "do" is a lowish level tone)

oho ... an exclamation of awe ("o" is a normal high tone, "ho" starts quite high and rises to the normal high tone level)

..... Word structure "nandau"

All nandau are what are called "content words"⁕ (LINGUISTIC JARGON). They are words like "house', or "run" or "beautiful" that have a definite meaning embedded in themselves.

If you look in the nandauli⁕⁕ (dictionary) you will get a form such as hend-. This is what is also called a pyabu.

Actually the original meaning of pyabu⁕⁕⁕ was "knot". It's meaning then spread to "entry" (in a ledger for example) or "item" (in a list for example). Then it spread to such forms as hend-. If you add a tail to a pyabu you get a nandau. For example henda = "to wear" is a landau, or hendo = "an item of clothing'" is also a nandau

Each pyabu is defined by 3 juzmia.

juzmi can be translated as "gesture", "a definite movement given a meaning by socially agreed convention", it also is used for the three parts that define a pyabu.

The three parts are juzmi @aba (the first gesture), juzmi @iga (the second gesture) and juzmi @oda (the third gesture).

The rule for determining what is a nandau and what is not (and by definition "what is not" => yadau), is that there must be one, and ONLY one jwavo in the three gestures.

jwavo = "molecule made from more than one element" or "consonant cluster" or "diphthong"

⁕A small number of yadau are also "content words". Invariable they are very common words. For example dunu "brown" or hiaᴴ "red".

⁕⁕nandauli is a good example of Limbawa word building. toili = book, nandau = word, toili nandaun = book of words. However if two words such as these occur together many times and/or their meaning starts to take on nuances which are more than the sum of the two components, then the two words coalesce . toili nandaun => nandauli (you get rid of the genitive n, swap the order of the two words and finally delete all but the final consonant and vowel of the second word)

⁕⁕⁕It is thought that when multiplication tables were invented, a name for each "entry" was sought. The adoption of pyabu came about thru analogy to a fishing net (multiplication tables are called "multiplication nets" by the way). The word later spread to 1D systems (i.e. items on a list) and to 3D systems (well the nandauli is one example)

⁕⁕⁕⁕By the way kyamo = "molecule made from only one element" or "geminate" or "long vowel" (where long vowels contrast with short vowels to produce minimal pairs)

.... the first element "juzmia @aba"

There are 37 juzmia @aba. Some of them are "kolta" (consonants in this case) and some of them are jwavo(meaning consonant clusters in this case). All the juzmia @aba are "complex sounds"(consonant or consonant clusters).

| @ | |||

| m | my | ||

| y | |||

| j | jw | ||

| f | fy | fl | |

| b | by | bl | bw |

| g | gl | gw | |

| d | dw | ||

| l | |||

| c | cw | ||

| s/ʃ | sl | sw | |

| k | ky | kl | kw |

| p | py | pl | |

| t | tw | ||

| w | |||

| n | ny | ||

| h |

.... the second element "juzmia @iga"

There are 9 juzmia @iga. Some of them are kolta (vowels in this case) and some of them are jwavo (diphthongs in this case). All juzmia @iga are "simple sounds"(vowels or diphthongs).

The juzmia @iga order is e, eu, u, au, a, ai, i, oi, o

.... the third element "juzmia @oda"

There are 58 juzmia @oda. Some of them are "single sounds" (consonants) and some of them are jwavo (consonant clusters in this case). All the juzmia @oda are "complex sounds"(consonant or consonant clusters).

| l@ | lm | ly | lj | lf | lb | lg | ld | lc | lz/lʒ | lk | lp | lt | lw | ln | lh | |

| @ | m | j | v | b | g | d | l | c | z/ʒ | k | p | t | n | h | ||

| n@ | ny | nj | nf | mb | ŋg | nd | nc | nz/nʒ | ŋk | mp | nt | mw | nh | |||

| s@ | zm | ʒy | zb | zg | zd | zl | sk | sp | st | zw | zn | sh |

The juzmia @oda order is l@, lm ... ln, lh, @, m ... n, h, n@, ny ... mw, nh, s@, zm ... zn, sh

..... Particles "yadau" and "yauyadau"

Most yadau are what are called "particles" in linguistics. These are the short words such as "the", "to", "because" that impart meaning to the nandaua around them, or specify the relation between two nandaua, or add a certain nuance/meaning to the whole utterance.

Examples of yadau are foi that is cliticized to the end of the first word of a sentence (thereby turning the sentence into a question). And mo which goes directly in front of a verb and negates the whole utterance. All the pronouns are also yadaua. All affixes⁕ also.

All words that are not a nandau are either yadau or yauyadau. yadau are mono-syllabic and possess either a high tone or a low tone. yauyadau are poly-syllabic and have neutral tone.

⁕In Limbawa an affix is called a "part yadau" (as opposed to all the non-affixes which are called "whole yadau")

..... The extended word "geudidau"

geudidau means extended word. It is also a good example of an extended word, in itself.

geuda is a verb meaning to extend in one direction (usually not up). geudo is an noun meaning an extension or appendix. geudi is an adjective meaning extended.

nandau geudi = extended word ... now when a noun and a following adjective occur together a lot (and maybe take on a meaning slightly different) the concept they represent is normally upgraded to a word, by deleting all but the last CV (consonant vowel) in the first word, and sticking this CV on to the end of the second word.

Hence we get geudidau. In theory there is no limit to the combinations that can occur. However in practice (outside of technical language) there are slightly under a hundred different CV's, and the number of elements that every CV can combine with, varies from 3 or 4 up to about 40.

In English we have a number of common endings, such as "-ism", "-ology", "ist", etc. etc. In Limbawa the end-stuck CV's can be thought of as equivalent to these English endings : the main difference is that this word building process is much more prevalent in Limbawa.

The CV -dau (from nandau) is found in combination with a number of other elements. For example ;-

du = to do, an action, a deed ... nandau dun = a word of action => dudau = a verb ... note that the n of dun has been deleted as well.

cwipa = an object, a thing(physical) ... nandau cwipan = an object word => cwipadau = a noun

sai. = a colour ...nandau sain. = a word of colour => saidau = an adjective

Note that in the last example, the meaning of the extended word has shifted a bit with respect to the meaning of the original words.

It is possible to extend further an extended word. For example ;-

kaza is an adjective meaning compicated and also is a noun meaning "a complicated thing" or "a complex".

kaza cwipadaun = a complex of a noun => cwipadauza = a noun phrase

And one more example ;-

limba = tongue or language. myega = a body of knowledge, the study. myega limban =>lumbaga = linguistics

..... Plurals and duals

In LIMBAWA the basic noun is undefined as to number. For example the plain noun báu could refer to any number of men. You can optionally use the plural form bawa to indicate a number more than one. To unequivocally refer to just one man, the word aba "one" must be included. i.e. aba báu = one man

báu = man or men

aba báu = one man

bawa = men

Most nouns end in one of the vowels a i u e or o.

To make a plural, these vowels undergo the following transformation.

a => ai

i => ia

u => ua

e => eu

o => oi

There are 8 nouns (that name parts of the body) that have a dual form as well as a plural form. They are ;-

wá = eye

ela = ear

duva = arm or hand

poma = leg or foot

gluma = breast

jwuba = buttock

ploka = cheek

lolna = shoulder

The dual form is made by a => au. For these 8 words the plural form means "3 or more" as opposed to "2 or more".

Also there are some other word that have a dual.

glabu = person

glabua = people

glabau = a couple (not necessary married but the word gives a very strong connotation that the couple are intimate/having sexual relations)

kloga = shoe

klogau = a pair of shoes

A very small number of nandau end in ai or au. For plurality they take a(that is another syllable is added to the word). For example ;-

nandau = word, nandaua = words

moltai = doctor, moltaia = doctors

At least 3 single-syllable yadau have irregular plurals. These are ;-

glà = woman

gala = women

báu = man

bawa = men

Usually single-syllable words indicate plurality by having nò in front.

nò = number

..... Numbers

LIMBAWA uses base 12.

| one | aja | 1012 | ajau | 10012 | ajai |

| two | aufa | 2012 | ufau | 20012 | ufai |

| three | aiba | 3012 | ibau | 30012 | ibai |

| four | uga | 4012 | ugau | 40012 | agai |

| five | ida | 5012 | idau | 50012 | idai |

| six | ela | 6012 | ulau | 60012 | ulai |

| seven | oica | 7012 | icau | 70012 | icai |

| eight | eza | 8012 | ezau | 80012 | ezai |

| nine | oka | 9012 | okau | 90012 | okai |

| ten | iapa | 120 i.e.(10x12) | apau | 10x12x12 | apai |

| eleven | uata | 11x12 | atau | 11x12x12 | atai |

You will noticed that 12 numbers over eleven have been shortened. For example the "regular" form for 20 would be aufau, but this is actually ufau.

Also the number 6, ela has been shortened. This would have been eula if everything was perfectly regular.

In the above table, 10 is actually, of course 12 : 90 is (9x12)+0 => 108 etc. etc.

The numbers in the above table combine, to express every number from 1 -> 1727 in one word. For example ;-

| 54312 | idaigauba |

| 50312 | idaiba |

| 64012 | ulaigau |

| 7212 | icaufa |

| 612 | ela |

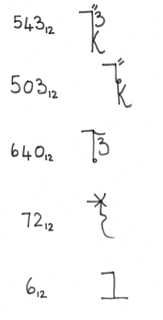

The above explains about the pronunciation of the numbers. But how are they written.

In fact the numbers are NEVER written out in full. See below for the characters corresponding to the five numbers above.

It can be seen that all the vowels are dropped and there is a horizontal line inserted in the top left of the character. The symbol for h is used for inserting zeroes (although never pronounced).

..... Pronouns

Limbawa is what is called an ergative language. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative. So let us explain what ergative means. Well in English we have 2 forms of the first person singular pronoun ... namely "I" and "me". Also we have 2 forms of the third person singular male pronoun ... namely "he" and "him". These two forms help determine who does what to whom. For example "I hit him" and "He hit me" have obviously different meanings (in English there is a fixed word order, which also helps. In Limbawa the word order is free).

timpa = to hit ... timpa is a verb that takes two nouns (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... a transitive verb).

pás ò timpari = I hit him pà ós timpori = He hit me ... OK in this case the protagonist marking in the verb also helps to make things disambiguous. But this will not always help, for example when both protagonists are third person singular.

So far so good. And we see that English and Limbawa behave in the same way so far. But what happens when we take a verb that takes only one noun (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... a transitive verb). For example doika = "to walk". In English we have "he walked". However in Limbawa we don't have *ós doikori but ò doikori (equivalent to saying "*him walked" in English). So this in a nutshell is what an ergative language is.

If you like you can say ;-

In English "him" is the "done to" : "he" is the "doer" and the "doer to".

In Limbawa ò is the "done to" and the "doer" : ós is the "doer to".

Below are two tables showing the two forms of the Limbawa pronouns.

| I | pás | we (includes "you") | yúas |

| we (doesn't include "you") | wías | ||

| you | gís | you (plural) | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ás | they | ás |

| me | pà | us | yùa |

| us | wìa | ||

| you | gì | you (plural) | jè |

| him, her | ò | them | nù |

| it | à | them | à |

There could be another member it the above table. When a action is performed by somebody on themselves, a special particle tí is used.

Just as in English, we do not say "*I hit me", but "I hit myself" ... in Limbawa we do not say *pás pà timpari, but pás tí timpari.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "myself" is what is called a "reflexive pronoun". In English there are many reflexive pronouns (i.e. "myself", "yourself", "herself", etc. etc.) : in Limbawa only one.

One other point ... Limbawa has generally a pretty free word order. But in a sentence such as jene tí laudori (Jane washed herself) it would be pretty unusual to have the tí before jene

..... 64 Adjectives

| good | bòi | bad | kéu |

| long | yàu | short | wái |

| high, tall | hái | low, short | ʔàu |

| happy, glad | ʔoime | sad, unhappy | heuno |

| white | ái | black | àu |

| young | sài | old (of a living thing) | gáu |

| clever, smart | jini | stupid, thick | tumu |

| near | nìa | far | múa |

| new | yaipe | old, former, previous | waufo |

| big | jutu | small | tiji |

| hot | fema | cold | pona |

| open | nafa | close | mapa |

| simple, easy | baga | complex, difficult, hard | kaza |

| sharp | naike | blunt | maubo |

| wet | nuco | dry | mide |

| empty | fene | full | pomo |

| fast | saco | slow | gade |

| strong | yubu | weak | wiki |

| heavy | hobua | light | ʔekia |

| beautiful | hauʔe | ugly | ʔaiho |

| contiguous, touching | yotia | apart, separate | wejua |

| fat | somua | thin, skinny | genia |

| bright | selia | dull, dim | golua |

| thin | pilia | thick | fulua |

| east, dawn, sunrise | cúa | west, dusk, sundown | dìa |

| tight | taitu | slack, loose | jauji |

| neat | ilia | untidy | ulua |

| soft | fuje | hard | pito |

| wide/broad | juga | narrow | tisa |

| rough | gaʔu | smooth | sahi |

| deep | gubu | shallow | siki |

| right | sèu | wrong | gói |

In the above list, it can be seen that each pair of adjectives have pretty much the exact opposite meaning. However in Limbawa there is ALSO a relationship between the sounds that make up these words.

In fact every element of a word is a mirror image (about the L-A axis in the chart below) of the corresponding element in the word with the opposite meaning.

| ʔ | ||||

| m | ||||

| y | ||||

| j | ia | |||

| f | e | |||

| b | eu | |||

| g | u | |||

| d | au | high tone (.) | ||

| l | ============================ | a | ============================ | neutral |

| c | ai | low tone | ||

| s/ʃ | i | |||

| k | oi | |||

| p | o | |||

| t | au | |||

| w | ||||

| n | ||||

| h |

12 colours

Here is the complete list of the colours of Limbawa.

| black | àu |

| white | ái |

| red | hìa |

| green | gèu |

| yellow | kiʔo |

| light blue | nela |

| dark blue | nelau |

| orange | suna |

| brown | dunu |

| pink | celai |

| purple | helau |

| grey | lozo |

.... verbs from adjectives

Any multi syllable adjective can become an r-form verb by simple dropping the last vowel (or diphthong) and adding the obligatory components that are needed. (See the next section)

gubu = deep, myigo = channel or canal,

guburi myigo = they deepened the canal

for the gamba the suffix du must be added.

gubudu = to deepen

All these derived verbs are transitive. That is they indicate the action is performed by one body on another body.

For the intransitive verbal meaning associated with these adjectives, the word selau (to become) must be used.

myigo gubu lori = the channel became deep (maybe by some sort of tidal activity) ... selau is one of the irregular verbs. Its r-form drops the initial se-

Any single syllable adjective, must have the suffix du in all its verbal forms. For example ;-

audu = to blacken, maŋkeu = faces

auduri maŋkiteu = they blackened their faces

PILANA

These are what in LINGUISTIC JARGON is called "cases".

The word pilana is built up from ;-

pila = to place, to position

pilana = positioning (this is an adjective made from pil + ana, in LINGUISTIC JARGON it is called a "present participle")

pilana = since in LIMBAWA, adjectives can be used as nouns, if pilana is found outside a NP (noun phrase ... the noun train components should be explained before now), and not as a copula complement, then it can be taken as a noun. Hence pilana = "the positioning one(s)"

Only a few of them live up to this name, never the less the whole set of 19 are called pilana in the LIMBAWA linguistic tradition.

The first 13 are suffixed to nouns. You could call these 13 plus the unmarked noun a case system of 14 cases. Well you could if you wanted to ... but there is no real reason.

Tha last 6 are a mixed bag. They perform the following operations ;-

| pronounced | operation | label | example |

| -kun | noun => noun | augmentive | nambokun = a mansion |

| -dia | noun => noun | diminutive | nambodia = a cottage |

| -ceu | noun => noun | "yucky" | namboceu = a hovel |

| -ma | adjective => noun | "-ness" or "-ity" | boima = goodness |

| -ve | adjective => adverb, plus noun => adverb | "-ly" | sacove = slowly, deutave = in the manner of a soldier |

| -gu | noun => adjective, plus adjective => adjective, plus verb => adjective | "ish" | gla.gu = effeminate, hia.gu = reddish, ??? |

We have 17 consonants in LIMBAWA. Only 2 are allowed to come at the end of a word ( -n and -s ). Hence if you see a word ending in a -p, for example, you know that there is some unwritten vowel that should follow. The pilana are partly an aid to quicker writing. Also they demarcate a set of 19 affixes and make quite a neat system. These are probably the 19 most common affixes although -ia and -ua are also quite common ( kloga = shoe klogia = shod klogua = shoeless )

Notice that -lya and -lfe are represented by a special amalgamated symbols which do not occur elsewhere.

The first 13 symbols could be part of a case system which assign a certain clausal* "roll" to the nouns to which they are connected .

Actually the first 13 symbols are only affixed if the NP is only one word. If the NP is more than one word, these affixes become independent particles that stand at the beginning of the NP. Of course they must be assigned a high or a low tone when they stand by themselves. These particles are ;-

pi

la

ya

fi

alya

alfe

ʔe

ho

wa

na or ni

swe

tu

ji

Notice that the second last pilana, is a symbol for "b" but is actually pronounced -ve. Mmm ... nobody knows why this is ... don't worry about it :-)

- Except for -n, -n defines its noun's roll within a NP (noun phrase).

PILANA ... in more detail

-ve

saco.ve = quickly ... actually if saco came immediately after the verb it was qualifying, it would always just be plain saco. However as the form saco.ve the adverb can move around the utterance ... wherever it wants to go.

When ve is prefixed to a noun, it can not be dropped if the resulting adverb immediately follows the verb.

deuta = soldier

doikora deuta.ve = he walk like a soldier

..... The main verb form (the r-form)

Now we take a typical verb to demonstrate the Limbawa verb system. doika meaning "to walk" or "the act of walking" will do.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In English the form of a verb which we use when we are talking about that verb, is called the "infinitive". The English infinitive seems to function pretty much like a noun, though it retains some verb-like characteristics. In Limbawa the form used (the recitation form) when we talk about a verb, is called gamba (meaning source or origin). It is fully a noun. For example kalme would be translated as "demolition" rather than "to demolish".

CENʔO

cen@o = musterlist, protagonist, list of characters in a play ... it is also the word used, for the vowel that is inserted immediately before the r in the r-form verb.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In the western linguistic tradition, these markers are said to represent "person" and "number". Person is either first, second or third person (i.e. I, you, he or she) and number refers to how the person changes when in the plural (sometimes dual also)

doikari = I walked

doikiri = You walked

doikori = He/She/It walked

doikuri = They walked

doikeri = You walked (this form is used when talking to more than one person)

doikauri = We walked (this form is used when the person spoken to, is not included in the "we")

doikairi = We walked (this form is used when the person spoken to, is included in the "we")

Note that the last form is used where in English you would use "you" or "one" (if you were a bit posh) ... as in "YOU do it like this", "ONE must do ONE'S best, mustn't ONE".

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... This pronoun is often called the "impersonal pronoun" or the "indefinite pronoun".

So we have 7 different forms for person and number.

GWOMA

gwoma is a verb meaning "to modify", "to alter", "to change one attribute of something'". It is a verbal noun so gwoma also means "modification".

gwomai (modifications) has a special meaning in LIMBAWA linguistics ... namely the nine suffixes which give tense and aspect information.

Here are the gwomai in the order that they are traditionally given.

1) doikari = I walked

This is the plain past tense. This is most often used when somebody is telling a story (a narrative). For example "Yesterday I got up, ate my breakfast and went to school". All three verbs in this narrative use the plain past tense.

2) doikarta = I have walked

While logically this doesn't have much difference from 1), it is emphasising a state rather than an action. It represents the state at the time of speaking as the outcome of past events. We have this tense/aspect in English and it is realized as "have xxxxen". For example if you wanted to talk to John and you went to his office, his secretary might say "he has gone to lunch" (as opposed to "he went for lunch"), which emphasises the absence of John.

Another use for this tense is to show that something has happened at least once in the past. For example "I have been to London".

3) doikarti = I had walked

This is similar to 2) except the time of relevance has shifted to the past. For example in a narrative if you wanted to explain the state of John at the party last night, you would say "When I met John, he had drunk eight cans of beer".

4) doikartu = I will have walked

This is similar to 3) except the time of relevance has shifted to the future.

5) doikaru = I will walk

This is the future tense. Of course you can never be 100% sure of the future. But (as in English) the future is dealt with in a similar way to the past.

6) doikara = I walk

In English "I walk" is usually called the "present tense" however this is a bit unfortunate. This is the form hat expresses timeless truths ... for example "birds fly". You could say this is the "default" gwomai.

7) doikarwi = I used to walk

doikarwi shows that you had many instances of walking in the past. For example "When I was a young girl, I used to walk 5 miles to school"

8) doikarwa = I usually walk

Note that in translating "I walk" from English into LIMBAWA, you have a choice of doikarwa or doikara. Generally the doikarwa form should be used if your possible walking time is interspersed with periods of non-walking. donarwa could be translated as "sometimes I walk, and sometimes I choose not to walk" or even "I usually walk".

9) doikarwu = I will walk, I will be walking

There is no exact equivalent to this on in English. Often confused with doikaru ( 5) ). Basically if the act of walking is just a one off ... for example in answer to the question "how are you going to the supermarket", doikaru would be used. But suppose that you had just moved to a new house, then the question "how will you get to the supermarket" is envisioning many instances of "walking" ... in that case, doikarwu would be used.

The above is an example of a "nuance" missing from English that LIMBAWA has. Below I give an example of a "nuance" that English has but which LIMBAWA lacks.

For example suppose two old friends from secondary school meet up again. One is a lot more muscular than before. He could explain his new muscles by saying "I have been working out". The "have" is appropriate because we are focusing on "state" rather than "action". The "am working out" is appropriate because it takes many instances of "working out" to build up muscles.

Every language has a limited range of ways to give nuances to an action, and language "A" might have to resort to a phrase to get a subtle idea across while language "B" has an obligatory little affix on the verb to economically express the exact same idea. You could swamp a language with affixes to exactly meet every little nuance you can think of (you would have an "everything but the kitchen sink" language). However in 99% of situations the nuances would not be needed and they would just be a nuisance.

(In Limbawa the muscle-bound schoolmate would probable use the "-rwa" form of the verb ; along with an adverb meaning "now")

Note ... if you say "I walk to church every Sunday" you have a choice of...

A) using doikarwa and dropping the Limbawa equivalent to "every".

B) using doikara and using the Limbawa equivalent to "every".

With (A) implying that you ONLY go on Sunday, whereas (2) leaves open the possibility that you go on other days of as well.

These suffixes are given in the chart below. The LIMBAWA terms for the different rows and columns are given. In the Western Linguistic tradition we would have ;-

Time => tense Behind => past Middle => present (although most people agree this is an unfortunate term) Ahead => future Aspect => aspect Completed => perfect Customary => habitual

LIMBAWA shows the imperfective aspect by prefixing the verb with the particle bai (see the section on Serial Verb Construction, to find out the origin of this particle)

bai doikari = I was walking

bai doikara = I am walking

bai doikaru = I will be walking

The most common use for this is when you want to fit another action, inside the act of walking. For example "I was walking to school when it started to rain". Occasionally this form is used when you simply want to emphasis that the action took a long time (well in Limbawa anyway, not so much in English). For example "This morning I was walking 2 hours to school (because I sprained my ankle)".

BELOW SOME RUBBISH

If the "modification" is something solid (something you can touch) then the form gwomo would be used. It is actually hard to draw the line between when gwoma should be used, and when gwomo should be used. But the linguistic usage falls just to the gwoma side of the line. Hence we talk about the Limbawa verb having 9 gwoma instead of 9 gwomo.

TENKO

tenkai is a verb, meaning "to prove" or "to testify" or "to give evidence" or "to demonstrate".

tenko is a noun derived from the above, and means "proof" or "evidence".

About a quarter of the worlds languages have, what is called "evidentiality", expressed in the verb. (It is unknown in Europe so most people have never heard of it) In a language that has "evidentials" you can say (or you must say) on what evidence you are saying what you are saying. In Limbawa there are 3 evidential affixes which can optionally be added to the verb.

doikori = He walked ... this is the neutral verb. The speaker has decided not to tell on what evidence he is stating "he walked".

doikorin = They say he walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because somebody (or some people) have told him so.

doikoris = I guess he walked ... It this case the speaker is asserting "he walked" because he worked it out somehow. (Maybe in this case he had seen that the "he" had muddy boots, and so later told a third person "he walked".

The above 2 tenko are introducing some doubt, compared to the plain unadorned form (doikori). The third tenko on the contrary, introduced more certainty.

doikoria = I saw him walk ... In this case the speaked saw the action with his own eyes. This form can also be used if the speaker witnessed the action thru' another of his senses (maybe thru' hearing for example), but in the overwhelming majority of cases where this form is used, it means "I saw it myself". This tenko can only be used with the "i" gwoma

7 cen@o (protagonist) which are obligatory.

9 gwoma (modifiers) which are obligatory.

3 tenko (proofs) which are optional.