LIMBAWA ... Chapter 1

..... The sounds of Limbawa

The full range of sounds heard in Limbawa are given below according to the conventions of the I.P.A. (International Phonetic Alphabet)

| labial | labiodental | alveolar | postalveolar | palatal | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stops | p b | t d | k g | ʔ | |||

| fricatives | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | h | |||

| affricates | tʃ dʒ | ||||||

| nasals | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| liquids | r l | ||||||

| glides | w | y |

tʃ dʒ are the initial sounds of "Charlie" and "Jimmy" respectively. From now on they will be represented by c and j.

ʔ represents a glottal stop (the sound a cockney would make when he drops the "tt" in bottle). In Limbawa this is a normal consonant ... just as real as "b" or "g" in English.

v is an allophone of f when inside a word and between two vowels.

z is an allophone of s when inside a word and between two voiced sounds.

ʃ is also an allophone of s when before the front vowel i or before the consonant y. ʃ is found in English and is usually represented by "sh" (as in "shell")

ʒ is an allophone of s when the above two conditions apply at the same time. ʒ turns up in English in one or two words. It is the middle consonant in the word "pleasure".

ŋ is an allophone of n when followed by k or g. ŋ is found in English and is usually represented by "ng" (as in "sing").

l is a clear lateral in all environments.

r is an approximant in all environments.

p, t and k are never aspirated. And on the other hand b, d and g are more voiced than in English (i.e. the voice onset time is a lot earlier)

The LIMBAWA phoneme inventory is shown below.

| labial | labiodental | alveolar | postalveolar | palatal | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stops | p b | t d | k g | ʔ | |||

| fricatives | f | s | h | ||||

| affricates | tʃ dʒ | ||||||

| nasals | m | n | |||||

| liquids | r l | ||||||

| glides | w | y |

The basic vowels are a, e, i, o and u. Also the diphthongs ai, au, oi, eu, ia and ua are used. Note that while the sounds ia and ua are possible sound combinations in English, they each are realised as two syllables. In Limbawa the two components are more intertwined ... the flow into each other more. And they each represent only one syllable.

It has been reported that Limbawa stresses the second to last syllable in a word. However this is untrue. This report came about because Limbawa speakers pronounce the second to last syllable of AN UTTERANCE, louder. This lead some linguistic field workers who were elicitating single words from the Limbawa speakers, to draw the wrong conclusions.

Limbawa differentiates between words using tone. All single syllable words have either a high tone (for example pás = "I") or a low tone (for example pà = me). All multi-syllable words lack tone (or can be said to have neutral tone). If a single syllable word, receives an affix making it into a multi-syllable word, its tone will become neutralised. If a word count was done on a typical LIMBAWA text, it would be found that around 17% of words have a high tone, 33% have a low tone and 50% have the neutral tone.

I am representing the high tone with a full-stop sign after the syllable (in a similar manner the Limbawa writing system places a small dot to the right of a high tone syllable). If single syllable words are come across that are not followed by a full-stop, they can be taken as low-tone (as happens in the native Limbawa writing system).

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "allophone", "voiced sound" and "diphthong" are linguistic jargon. You don't have to worry if you don't understand what they mean.

..... Some interjections

All languages have a small set of interjections. Usually they party fall outside the normal sound system rules. Limbawa is no exception.

iʃʃ ... an exclamation expressing sympathy (neutral tone)

xaa ... an exclamation of disgust (it starts of as a neutral tone, falls quickly then sort of lingers at a low level)...(the "x" represents the last sound in "loch")

aido ... an exclamation of frustration (rapidly rising tone on the "ai", a short break, then the "do" is a lowish level tone)

oho ... an exclamation of awe ("o" is a normal high tone, "ho" starts quite high and rises to the normal high tone level)

..... Consonant clusters

The following consonants and consonant clusters can begin a word;-

| ʔ | |||

| m | my | ||

| y | |||

| j | jw | ||

| f | fy | fl | |

| b | by | bl | bw |

| g | gl | gw | |

| d | dw | ||

| l | |||

| c | cw | ||

| s/ʃ | sl | sw | |

| k | ky | kl | kw |

| p | py | pl | |

| t | tw | ||

| w | |||

| n | ny | ||

| h |

The following consonants and consonant clusters can be found in the middle of a word;-

| l@ | lm | ly | lj | lf | lb | lg | ld | lc | lz/lʒ | lk | lp | lt | lw | ln | lh | |

| @ | m | j | v | b | g | d | l | c | z/ʒ | k | p | t | n | h | ||

| n@ | ny | nj | nf | mb | ŋg | nd | nc | nz/nʒ | ŋk | mp | nt | mw | nh | |||

| s@ | zm | ʒy | zb | zg | zd | zl | sk | sp | st | zw | zn | sh |

The consonants n and s can occur word finally.

..... Word building

⁕⁕nandauli is a good example of Limbawa word building. toili = book, nandau = word, toili nandaun = book of words. However if two words such as these occur together many times and/or their meaning starts to take on nuances which are more than the sum of the two components, then the two words coalesce . toili nandaun => nandauli (you get rid of the genitive n, swap the order of the two words and finally delete all but the final consonant and vowel of the second word)

geudidau means extended word. It is also a good example of an extended word, in itself.

geuda is a verb meaning to extend in one direction (usually not up). geudo is an noun meaning an extension or appendix. geudi is an adjective meaning extended.

nandau geudi = extended word ... now when a noun and a following adjective occur together a lot (and maybe take on a meaning slightly different) the concept they represent is normally upgraded to a word, by deleting all but the last CV (consonant vowel) in the first word, and sticking this CV on to the end of the second word.

Hence we get geudidau. In theory there is no limit to the combinations that can occur. However in practice (outside of technical language) there are slightly under a hundred different CV's, and the number of elements that every CV can combine with, varies from 3 or 4 up to about 40.

In English we have a number of common endings, such as "-ism", "-ology", "ist", etc. etc. In Limbawa the end-stuck CV's can be thought of as equivalent to these English endings : the main difference is that this word building process is much more prevalent in Limbawa.

The CV -dau (from nandau) is found in combination with a number of other elements. For example ;-

du = to do, an action, a deed ... nandau dun = a word of action => dudau = a verb ... note that the n of dun has been deleted as well.

cwipa = an object, a thing(physical) ... nandau cwipan = an object word => cwipadau = a noun

sái = a colour ...nandau sáin = a word of colour => saidau = an adjective

Note that in the last example, the meaning of the extended word has shifted a bit with respect to the meaning of the original words.

It is possible to extend further an extended word. For example ;-

kaza is an adjective meaning compicated and also is a noun meaning "a complicated thing" or "a complex".

kaza cwipadaun = a complex of a noun => cwipadauza = a noun phrase

And one more example ;-

limba = tongue or language. myega = a body of knowledge, the study. myega limban =>lumbaga = linguistics

..... Plurals and duals

In LIMBAWA the basic noun is undefined as to number. For example the plain noun báu could refer to any number of men. You can optionally use the plural form bawa to indicate a number more than one. To unequivocally refer to just one man, the word aba "one" must be included. i.e. aja báu = one man

báu = man or men

aja báu = one man

bawa = men

Most nouns end in one of the vowels a i u e or o.

To make a plural, these vowels undergo the following transformation.

a => ai

i => ia

u => ua

e => eu

o => oi

There are 8 nouns (that name parts of the body) that have a dual form as well as a plural form. They are ;-

wá = eye

elza = ear

duva = arm or hand

poma = leg or foot

gluma = breast

jwuba = buttock

ploka = cheek

olna = shoulder

The dual form is made by a => au. For these 8 words the plural form means "3 or more" as opposed to "2 or more".

Also there are some other word that have a dual.

glabu = person

glabua = people

glabau = a couple (not necessary married but the word gives a very strong connotation that the couple are intimate/having sexual relations)

kloga = shoe

klogau = a pair of shoes

A very small number of nandau end in ai or au. For plurality they take a(that is another syllable is added to the word). For example ;-

nandau = word, nandaua = words

moltai = doctor, moltaia = doctors

At least 3 single-syllable yadau have irregular plurals. These are ;-

glà = woman

gala = women

báu = man

bawa = men

Usually single-syllable words indicate plurality by having nò in front.

nò = number (actually this number has an irregular plural as well, nogi, which means "arithmetic" as well as "numbers".

..... Thread Writing

LIMBAWA has 17 consonants. For some of these the form differs slightly, depending upon whether the letter is at word initial, word medial or word final. The three forms are shown below.

LIMBAWA has 5 vowels and 6 diphthongs. These are also shown below.

..... Numbers

LIMBAWA uses base 12.

| one | aja | 1012 | ajau | 10012 | ajai |

| two | auva | 2012 | uvau | 20012 | uvai |

| three | aiba | 3012 | ibau | 30012 | ibai |

| four | uga | 4012 | ugau | 40012 | agai |

| five | ida | 5012 | idau | 50012 | idai |

| six | ela | 6012 | ulau | 60012 | ulai |

| seven | oica | 7012 | icau | 70012 | icai |

| eight | eza | 8012 | ezau | 80012 | ezai |

| nine | oka | 9012 | okau | 90012 | okai |

| ten | iapa | 120 i.e.(10x12) | apau | 10x12x12 | apai |

| eleven | uata | 11x12 | atau | 11x12x12 | atai |

You will noticed that 12 numbers over eleven have been shortened. For example the "regular" form for 20 would be auvau, but this is actually uvau.

Also the number 6, ela has been shortened. This would have been eula if everything was perfectly regular.

In the above table, 10 is actually, of course 12 : 90 is (9x12)+0 => 108 etc. etc.

The numbers in the above table combine, to express every number from 1 -> 1727 in one word. For example ;-

| 54312 | idaigauba |

| 50312 | idaiba |

| 64012 | ulaigau |

| 7212 | icauva |

| 612 | ela |

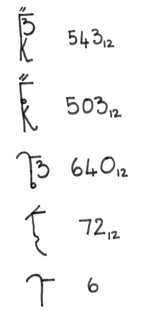

The above explains about the pronunciation of the numbers. But how are they written.

In fact the numbers are NEVER written out in full. See below for the characters corresponding to the five numbers above.

It can be seen that all the vowels are dropped and there is a horizontal line inserted in the top left of the character. The symbol for h is used for inserting zeroes (although never pronounced).

If you had a leading zero you would use the word jù which is usually placed before nouns and means "space/empty/zero/no". 007 would be jù jù oica (three words)

To deal with a telephone number, you would lump the numbers in threes (any leading zero by itself though) and outspeak the numbers. If you were left with a single digit (say 4) it would be pronounced agai. If you were to pronounce it uga, it would of course mean 004. Also you would probably add the particle dó at the end. This means "exactly" (or it can mean the speaker has finished outspeaking the number)

..... Pronouns

Limbawa is what is called an ergative language. About a quarter of the world languages are ergative or partly ergative. So let us explain what ergative means. Well in English we have 2 forms of the first person singular pronoun ... namely "I" and "me". Also we have 2 forms of the third person singular male pronoun ... namely "he" and "him". These two forms help determine who does what to whom. For example "I hit him" and "He hit me" have obviously different meanings (in English there is a fixed word order, which also helps. In Limbawa the word order is free).

timpa = to hit ... timpa is a verb that takes two nouns (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... a transitive verb).

pás ò timpari = I hit him pà ós timpori = He hit me ... OK in this case the protagonist marking in the verb also helps to make things disambiguous. But this will not always help, for example when both protagonists are third person singular.

So far so good. And we see that English and Limbawa behave in the same way so far. But what happens when we take a verb that takes only one noun (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... a transitive verb). For example doika = "to walk". In English we have "he walked". However in Limbawa we don't have *ós doikori but ò doikori (equivalent to saying "*him walked" in English). So this in a nutshell is what an ergative language is.

If you like you can say ;-

In English "him" is the "done to" : "he" is the "doer" and the "doer to".

In Limbawa ò is the "done to" and the "doer" : ós is the "doer to".

Below are two tables showing the two forms of the Limbawa pronouns.

| I | pás | we (includes "you") | yúas |

| we (doesn't include "you") | wías | ||

| you | gís | you (plural) | jés |

| he, she | ós | they | nús |

| it | ás | they | ás |

| me | pà | us | yùa |

| us | wìa | ||

| you | gì | you (plural) | jè |

| him, her | ò | them | nù |

| it | à | them | à |

There could be another member it the above table. When a action is performed by somebody on themselves, a special particle tí is used.

Just as in English, we do not say "*I hit me", but "I hit myself" ... in Limbawa we do not say *pás pà timpari, but pás tí timpari.

LINGUISTIC JARGON ... "myself" is what is called a "reflexive pronoun". In English there are many reflexive pronouns (i.e. "myself", "yourself", "herself", etc. etc.) : in Limbawa only one.

One other point ... Limbawa has generally a pretty free word order. But in a sentence such as jene tí laudori (Jane washed herself) it would be pretty unusual to have the tí before jene

There is an emphatic particle yá which is usually placed after the element that has to be emphasized. However with the pronouns, the particle and the pronouns have been fused together, giving the following forms;-

| me myself | paya | we ourselves | yuaya |

| we ourselves | wiaya | ||

| you yourself | giya | you yourselves | jeya |

| him himself, her herself | oya | them themselves | nuya |

| it itself | aya | them themselves | aya |

And any of the pilana can be added to the above forms. For example payas ò timaru => I myself will hit her

..... 64 Adjectives

| good | bòi | bad | kéu |

| long | yàu | short | wái |

| high, tall | hái | low, short | ʔàu |

| happy, glad | ʔoime | sad, unhappy | heuno |

| white | ái | black | àu |

| young | sài | old (of a living thing) | gáu |

| clever, smart | jini | stupid, thick | tumu |

| near | nìa | far | múa |

| new | yaipe | old, former, previous | waufo |

| big | jutu | small | tiji |

| hot | fema | cold | pona |

| open | nafa | close | mapa |

| simple, easy | baga | complex, difficult, hard | kaza |

| sharp | naike | blunt | maubo |

| wet | nuco | dry | mide |

| empty | fene | full | pomo |

| fast | saco | slow | gade |

| strong | yubu | weak | wiki |

| heavy | hobua | light | ʔekia |

| beautiful | hauʔe | ugly | ʔaiho |

| contiguous, touching | yotia | apart, separate | wejua |

| fat | somua | thin, skinny | genia |

| bright | selia | dull, dim | golua |

| thin | pilia | thick | fulua |

| east, dawn, sunrise | cúa | west, dusk, sundown | dìa |

| tight | taitu | slack, loose | jauji |

| neat | ilia | untidy | ulua |

| soft | fuje | hard | pito |

| wide/broad | juga | narrow | tisa |

| rough | gaʔu | smooth | sahi |

| deep | gubu | shallow | siki |

| right | sèu | wrong | gói |

In the above list, it can be seen that each pair of adjectives have pretty much the exact opposite meaning. However in Limbawa there is ALSO a relationship between the sounds that make up these words.

In fact every element of a word is a mirror image (about the L-A axis in the chart below) of the corresponding element in the word with the opposite meaning.

| ʔ | ||||

| m | ||||

| y | ||||

| j | ia | |||

| f | e | |||

| b | eu | |||

| g | u | |||

| d | au | high tone (.) | ||

| l | ============================ | a | ============================ | neutral |

| c | ai | low tone | ||

| s/ʃ | i | |||

| k | oi | |||

| p | o | |||

| t | au | |||

| w | ||||

| n | ||||

| h |

... The 12 colours

Here is the complete list of the colours of Limbawa.

| black | àu |

| white | ái |

| red | hìa |

| green | gèu |

| yellow | kiʔo |

| light blue | nela |

| dark blue | nelau |

| orange | suna |

| brown | dunu |

| pink | celai |

| purple | helau |

| grey | lozo |

... Parts of speech and word order ... part 1

The main parts of speech in LIMBAWA are nouns, verbs and adjectives (there are others but these three are the main ones). First let us consider adjectives and how they can act as nouns and verbs.

Let us take the word gèu "green" which is fundamentally an adjective. However the unmodified word can also be a noun in certain positions. It can mean "the green one" (what I call a substantive) or it can mean "greenness" (what I call a qualitative). So how do we know if gèu represents an adjective, or a substantive noun , or a qualitative noun ? Well we can tell by the position of gèu with respect to other elements in the clause.

gèu is an adjective if it comes immediately after the copula sàu. For example báu rì gèu => The/a man was green.

gèu is also an adjective if it comes immediately after a noun i.e. báu gèu dí => This green man *

gèu is a qualitative noun if it comes immediately after the copula gaza i.e. ʔá pona => It is cold ..... ʔá pona paʔe => I am cold ... (O.K. we had to use a different adjective to demonstrate this one)

In other positions, if you want to express the qualitative noun, you must add the pilana -ma i.e. geuma => greenness

In all other positions gèu is a substantive noun i.e. it means "a/the green one" which will either have human or non-human reference, depending on context.

For gèu to be an verb, it needs to be modified i.e. geudu => to make green, to greenify **

(pás) tí gedari => I made mysef green

(pà) lari gèu => I became green

pà geudari => I became green ??? Is THIS my passive (not a proper passive), some sort of middle voice ??? what about LABILES ?

- By the way, if you want to qualify a noun with two adjectives, you must use a relative clause i.e. báu tà gèu té jutu => The/a big and green man

- By the way dú is a verb meaning "do"

gubu = deep, myigo = channel or canal,

gubuduri myigo = they deepened the canal

for the gamba the suffix du must be added.

gubudu = to deepen

All these derived verbs are transitive. That is they indicate the action is performed by one body on another body.

For the intransitive verbal meaning associated with these adjectives, the word selau (to become) must be used.

myigo gubu lori = the channel became deep (maybe by some sort of tidal activity) ... selau is one of the irregular verbs. Its r-form drops the initial se-

Any single syllable adjective, must have the suffix du in all its verbal forms. For example ;-

audu = to blacken, maŋkeu = faces

auduri maŋkiteu = they blackened their faces

... The cases ... PILANA

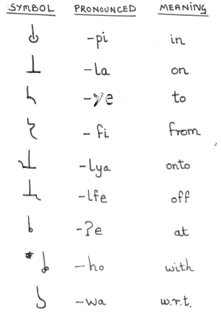

These are what in LINGUISTIC JARGON is called "cases".

The word pilana is built up from ;-

pila = to place, to position

pilana = positioning (this is an adjective made from pil + ana, in LINGUISTIC JARGON it is called a "present participle")

pilana = since in LIMBAWA, adjectives can be used as nouns, if pilana is found outside a NP (noun phrase ... the noun train components should be explained before now), and not as a copula complement, then it can be taken as a noun. Hence pilana = "the positioning one(s)"

Only a few of them live up to this name, never the less the whole set of 19 are called pilana in the LIMBAWA linguistic tradition.

The first 13 are suffixed to nouns. You could call these 13 plus the unmarked noun a case system of 14 cases. Well you could if you wanted to ... but there is no real reason.

Tha last 4 are a mixed bag. They perform the following operations ;-

| pronounced | operation | label | example |

| -cauze | noun => noun | ||

| -ma | adjective => noun | "-ness" or "-ity" | boima = goodness |

| -ve | adjective => adverb, plus noun => adverb | "-ly" | sacove = slowly, deutave = in the manner of a soldier |

| -go | noun => adjective, plus adjective => adjective, plus verb => adjective | "ish" | gla.gu = effeminate, hia.gu = reddish, ??? |

We have 17 consonants in LIMBAWA. Only 2 are allowed to come at the end of a word ( -n and -s ). Hence if you see a word ending in a -p, for example, you know that there is some unwritten vowel that should follow. The pilana are partly an aid to quicker writing. Also they demarcate a set of 19 affixes and make quite a neat system. These are probably the 19 most common affixes although -ia and -ua are also quite common ( kloga = shoe klogia = shod klogua = shoeless )

Notice that -lya and -lfe are represented by a special amalgamated symbols which do not occur elsewhere.

The first 13 symbols could be part of a case system which assign a certain clausal* "roll" to the nouns to which they are connected .

Actually the first 13 symbols are only affixed if the NP is only one word. If the NP is more than one word, these affixes become independent particles that stand at the beginning of the NP. Of course they must be assigned a high or a low tone when they stand by themselves. These particles are ;-

| -pi | pi |

| -la | la |

| -ye | ye |

| -vi | fi |

| -lya | alya |

| -alfe | alfe |

| -ʔe | ʔe |

| -ho | ho |

| -wa | wa |

| -n | na or ni |

| -s | swe |

| -tu | fu |

| -ji | jia |

Notice that the second last pilana, is a symbol for "b" but is actually pronounced -ve. Mmm ... nobody knows why this is ... don't worry about it :-)

- Except for -n, -n defines its noun's roll within a NP (noun phrase).

-pi

-la

-ye

-vi

-lya

-lfe

-ʔe

-ho

-wa

-n

-s

-tu

-ji

-cauze

-ma

ve

-go

-ʔe

-n

na = of

The particle na before a noun makes a sort of adjective construction with this noun. For example kyolo na kaunu di. = "the collar of this coat".

The particle ni before a noun, behaves in a similar way. However with ni the meaning is strictly "possession" and the noun must be human. For example kaunu hia ni jene = Jenny's red coat

When the noun is a single word (LINGUISTIC JARGON ... that is when it is a simple noun instead of what is called "a noun phrase". kaunu di and kaunu hia are two example of what is called a "noun phrase". kaunu hia di "this red coat" is another example) -n can be stuck on to the end of a word (instead of na or ni going before the word) to give an adjective.

So instead of saying kyolo na kaunu we would say kyolo kaunun

Instead of saying kaunu ni jane we would say kaunu jenen

The noun that is qualified by a noun, can itself qualify yet another noun. For example ;-

fanfa sondan blicon = "the horse of the son of the king" or "the king's son's horse"

However if any of these nouns is qualified by an adjective, then n can not be suffixed, but the forms na or ni must be used. For example ;-

fanfa ni sonda jini blicon = "the horse of the king's clever son

fanfa sondan na blico somua = "the horse of the fat king's son" ... ?? why so ... also how would this interact with the -ana form which is really an adjective, but becomes a noun quite easily ??

(LINGUISTIC JARGON ... In the above 2 examples kaunu and jane would be said to be in the genitive case. Many languages have a genitive case)

With pronouns things are slightly different. Forms such as *ni pa are not used. n is suffixed to the pronouns but the result is a noun.

pan = "(the) thing that belongs to me" or "mine".

The table below gives these "nouns" that are derived from the pronouns ... all are perfectly regular.

| mine | pan | ours | yuan |

| ours | wian | ||

| yours | gin | yours (plural) | jen |

| his, hers | non | theirs | nun |

This is a special construction that relates pronouns to gamba. For example ;-

wí = to see polo = Paul timpa = to hit jene = Jenny

wori timpa polon = He saw paul hitting

wori timpa pan na ò = He saw me hitting her

wori timpa na jene = He saw Jenny being hit

wori timpa polon na jene = He saw Paul hitting Jenny ... it is actually pronounced as wori timpa polonna jene with the -nn- pronounced the same way as you would pronounce -nn- in the English word "keanness".

wori timpa pan na jene = He saw me hitting Jenny.

For a normal noun, pan would never directly follow, qualifying that noun. The noun would be split and the infix -ap- inserted. However the gamba can never be split and an infix inserted (see next section). (at least I don't think so ... read up about the Finnish infinites)

In the above constructions the word order must be as shown above.

-ho

-wa

-ve

saco.ve = quickly ... actually if saco came immediately after the verb it was qualifying, it would always just be plain saco. However as the form saco.ve the adverb can move around the utterance ... wherever it wants to go.

When ve is prefixed to a noun, it can not be dropped if the resulting adverb immediately follows the verb.

deuta = soldier

doikora deuta.ve = he walk like a soldier

blá = to quarrel

gala rá bla.ve = the women are quarrelsome