LIMBAWA ... Chapter 1.5: Difference between revisions

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

O.K. this number has a ridiculous dynamic range. But this is for demonstration purposes only: if you can handle this number you can handle any number. Remember the number is in base 12. | O.K. this number has a ridiculous dynamic range. But this is for demonstration purposes only: if you can handle this number you can handle any number. Remember the number is in base 12. | ||

This monster would be pronounced '''aja huŋgu | This monster would be pronounced '''aja huŋgu uvaila nàin ezaitauba wúa idauja omba idaizaupa yanfa elaibau mulu idaidauka ʔiwetu elaivau dó''' | ||

Now the 7 "placeholders" are not really thought of as real numbers, they are markers only. The LIMBAWA community has a very strong feeling that there are only 1727 proper numbers. You never see (the LIMBAWA equivalent of) "a thousand" or "a million". Rather you would hear "ONE thousand exactly", or "ONE thousand approximately". (Actually I tell a lie, there are a number of sayings, where you can hear "ONE thousand" etc. etc.) | Now the 7 "placeholders" are not really thought of as real numbers, they are markers only. The LIMBAWA community has a very strong feeling that there are only 1727 proper numbers. You never see (the LIMBAWA equivalent of) "a thousand" or "a million". Rather you would hear "ONE thousand exactly", or "ONE thousand approximately". (Actually I tell a lie, there are a number of sayings, where you can hear "ONE thousand" etc. etc.) | ||

Revision as of 05:54, 15 August 2012

..... LOGI

Above right you can see the numbers 1 -> 11 displayed. Notice that the forms of 7 and 9 have been simplified (also 1 and 6 in a minor way).

In the bottom right you can see 7 interesting symbols. These are used to extend the range of the LIMBAWA number system (remember the basic system only covers 1-> 1727). Their meanings are given in the table below.

| elephant | huŋgu |

| rhino | nàin |

| water buffalo | wúa |

| circle | omba |

| hare | yanfa |

| beetle | mulu |

| bacterium, bug | ʔiwetu |

To give you an idea of how they are used, I have given you a very big number below.

O.K. this number has a ridiculous dynamic range. But this is for demonstration purposes only: if you can handle this number you can handle any number. Remember the number is in base 12.

This monster would be pronounced aja huŋgu uvaila nàin ezaitauba wúa idauja omba idaizaupa yanfa elaibau mulu idaidauka ʔiwetu elaivau dó

Now the 7 "placeholders" are not really thought of as real numbers, they are markers only. The LIMBAWA community has a very strong feeling that there are only 1727 proper numbers. You never see (the LIMBAWA equivalent of) "a thousand" or "a million". Rather you would hear "ONE thousand exactly", or "ONE thousand approximately". (Actually I tell a lie, there are a number of sayings, where you can hear "ONE thousand" etc. etc.)

When first introduced to this system, many people think that the LIMBAWA culture must be untenable, however strangely enough the LIMBAWA culture has lasted many thousands of year, despite the obvious confusion that must arise when they attempt to count elephants.

One further point ...

If you wanted to express a number represented by digits 2->4 from the LHS of the monster, you would say aufaidaula nàin .... the same way as we have in the Western European tradition. However if you wanted to express a number represented digits 6 ->8 from the RHS of the monster, you would say yanfa elaibau .... not the way we do it. This is like saying "milli 630" instead of "630 micro".

Ah that is another thing ... the units used either come at the end (or they can replace omba (which means "unit" as well as "circle", by the way)).

..... SAINO

saino = day

The LIMBAWA day begins at sunrise. 6 o'clock in the morning is called cuaju

The time of day is counted from cuaju. 24 hours is considered one unit. 8 o'clock in the morning would be called ajai (normally just called ajai, but cúa ajai or omba ajai might also be heard sometimes. 10 o'clock in the morning would be called auvai

| 6 o'clock in the morning | cuaju |

| 8 o'clock in the morning | ajai |

| 10 o'clock in the morning | uvai |

| midday | aibai |

| 2 o'clock in the afternoon | agai |

| 4 o'clock in the afternoon | idai |

| 6 o'clock in the evening | ulai |

| 8 o'clock in the evening | icai |

| 10 o'clock at night | ezai |

| midnight | okai |

| 2 o'clock in the morning | apai |

| 4 o'clock in the morning | atai |

Ten past 4 o'clock in the afternoon would be called idaijau twenty past four would be idaivau Half past four would be idaibau ... and so on up to 6 o'clock.

All these names have the element idai in common, hence the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock is called idaia (the plural of idai). This is exactly the same as us calling the period from 1960 -> 1969, "the sixties".

If something happened in the period from 4 o'clock to 6 o'clock, it would be said to have happened idaia.pi

Usually you talk about points of time rather than periods of time. If you arrange to meet somebody at 2 o'clock morning, you would meet them apaiʔe.

But we refer to periods of time occasionally. If some action continued for 20 minutes, it will have continued nàn uvau, for 2 hours : nàn ajai (nàn means "a long time")

Originally there was no word as such for a 2 hour period. However

2 hour period = aia ? ... 10 minute period = aua ?

The perion from 6 o'clock to 8 o'clock in the morning is called cuajua ... a back formation.

The Calendar

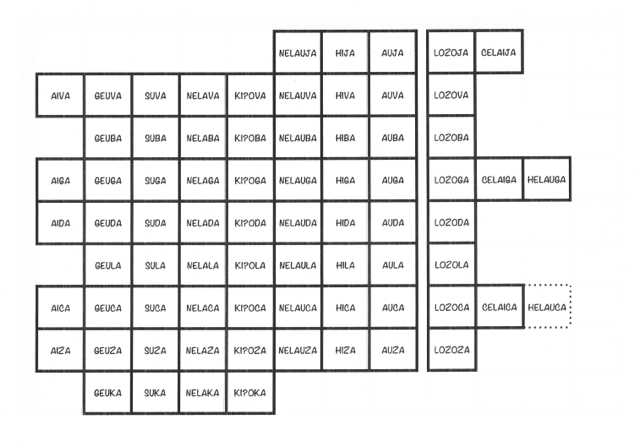

The LIMBAWA month is quite interesting. It has 73 days. The first day of the month is nelauja followed by hija, then auja lozoja celaija and then aiva etc. etc.

The days to the right are workdays while the days to the left are days off work. Each month has a special festival associated with it. These festivals are held in the perion lozoga, celaiga, helauga.

By the way, when a year changes, it doesn't change between months, it changes between lozoga and celaiga.