Piscean language

Piscean (Piscean: pisceesum) is the official language of the proposed New Piscean Workers' Nation, founded on the manmade island New Pisces - off the coast of western France - that is said to be created in 2028. Despite being the constructed language of Representative S.C. Anderson, Piscean is linguistically derived from Old English and modern German; however, it is written not with the Latin or runic alphabets, but with the 'pro-Phoenician' Andersonic writing system devised in 2007. (For the purpose of this article, examples of Piscean will be transliterated into the Latin alphabet.) The official ancestor of Piscean is late Old Piscean, which provided the foundation for the modern dialect that would take on even more influence from German, yet would also make Old English the dominant source.

Contents

Pronunciation

Piscean uses the standard pronunciation of the Andersonic alphabet (see here). Vowels are short if they are followed by a double consonant or long if they are followed by either a single consonant or no consonant, e.g. the I in 'icc' is pronounced like 'thick', noting the double C, whereas the I in 'bit' is pronounced like 'eat'.

Note the exceptions:

- E at the end of a Piscean word is equivalent to a schwa /ə/ like English 'winner'.

- EN at the end of a Piscean word is equivalent to a schwa /ə/ followed by /n/ like English 'garden'

- JN at the beginning of a Piscean word is pronounced as EN - above

- ER within a Piscean word is /ɛə/ like English 'hair'

- EST within a Piscean word is /ɛ st/ like English 'best'

- EL within a Piscean word is /ɛ l/ like English 'help'

- AN at the end of a verb infinitive is /æ n/ like English 'ban'

- F as the initial or final letter of a Piscean word is /f/ as it is in English, but ...

- F anywhere else inside a Piscean word is /v/ like English 'voice'

Dipthongs and multigraphs

Piscean also uses various dipthongs and multigraphs like letters in their own right, albeit not considered part of the alphabet.

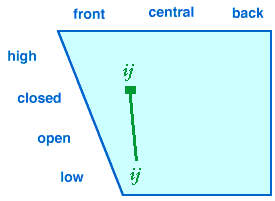

- ij /aɪ/ like 'kite'

- ow /aʊ/ like 'house'

- oj /ɔɪ/ like 'join'

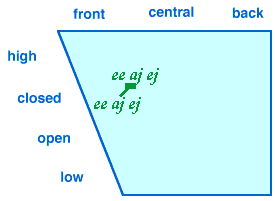

- ee; aj; ej /eɪ/ like 'pain'

- sch /ʃ/ like 'shop'

- tsch /tʃ/ like 'chair'

- scg /dʒ/ like 'edge'

Phonology

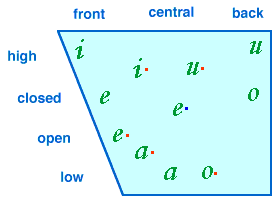

Vowels

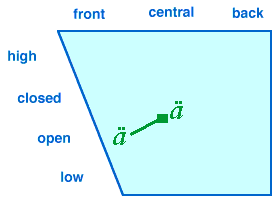

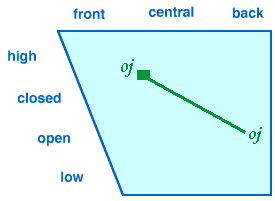

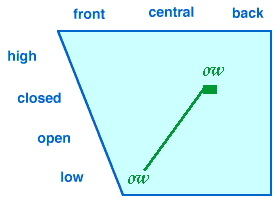

Vowels followed by a red mark are those sounds that are used if the vowel is followed by a double consonant. The blue mark next to the E indicates that the sound only appears as the final letter of a Piscean word. There are several dipthongs in Piscean, in addition to Ä, which behaves like a dipthong in the way it is a transition from one vowel sound to another. These are depicted below as maps, where the green lines portray the journeys of the sounds and the square indicates the destination sound.

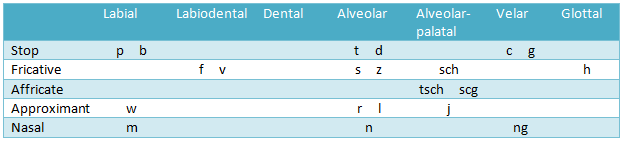

Consonants

Stress

Stress in Piscean usually falls on the first syllable, with the following exceptions:

- Verbs of the '-eeran' group receive stress on their penultimate syllable.

- Similarly, nouns of the '-eerung' group receive stress on their penultimate syllable.

- Verbs beginning with the prefixes a-, ond-, bi-, for-, ge-, ofer-, on-, to-, un-, under-, ijmb-, of-, full-, fram-, in-, fort-, mid-, eefter-, befor-, eet-, ongän-, gäder-, feest-, efen- and jeond- receive stress on the first syllable that comes after the prefix. For example, in 'efenmacian' ('to make equal'), the stress is placed on the syllable 'mac'.

- Words in which vowels are marked with acute accents. These are commonly found in words to retain the stress from the original source language (if it differs from Piscean stress rules), especially names of countries, which have been derived from several languages. An acute accent marks the vowel that belongs to the stressed syllable. For exmaple, in 'Américo' (America), the stress is placed on the syllable 'er'. In 'Scgipún' (Japan), the stress is placed on 'pun'.

Articles

The Piscean language includes three 'logical' grammatical genders. While in many languages, the genders do not often relate to physical properties of nouns, they do in Piscean; therefore, most nouns are neuter, while creatures of the male sex are masculine and creatures of female sex are feminine. If one refers to a creature, but does not wish to distinguish sex, the neuter gender can be used as a substitute. Observe the following examples:

- teet Sunne - the sun (no sex, so neuter)

- teet Mann - the person (no sex specified, so neuter)

- se Mann - the man (male, so masculine)

- seo Mann - the woman (female, so feminine)

The above example shows the importance the article plays in Piscean of distinguishing between sexes in a language where one noun fits all.

Definite article

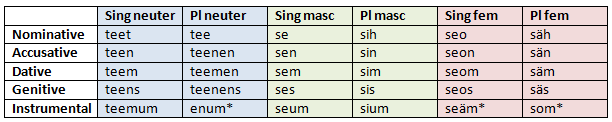

The definite article is inflected in various ways, firstly split into three depending on grammatical gender, then into six depending also on quantity - whether singular or plural - and finally into a further thirty depending on grammatical case - whether nominative, accusative, dative, genitive or instrumental.

Those words highlighted with an asterisk follow irregular patterns. 'Enum' is a contraction arising from a rather complex - and now incorrect - 'teemenum'. 'Seäm' is a result of 'seoum', which is difficult for a Piscean speaker to pronounce. The O and U thus collapse into Ä. Similarly, 'som' is contrived, as 'säum' is awkward in speech, giving way instead to a collapse of Ä and U into O.

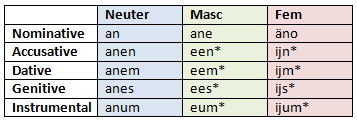

Indefinite article

The indefinite article (in English, 'a/an') is inflected in much the same way as the definite article, but lacking plural forms (which are shown not with an article, merely by inflecting the noun itself).

Those words highlighted with an asterisk follow irregular patterns. 'Een', 'eem', 'ees' and 'eum' are contracted forms of 'aneen', 'aneem', 'anees' and 'aneum', respectively. Regarding the feminine irregularities, 'änoen', 'änoem', 'änoes' and 'änoum' first contracted to 'oen', 'oem', 'oes' and 'oum', but - for even easier pronunciation - the O (and E, where applicable) finally collapsed into the dipthong IJ, which sounds like the English word 'eye'.

Cases and prepositions

Piscean implements five cases: nominative, accusative, dative, genitive and instrumental. Anderson affirms that these have greatly important and stylistic purposes.

Nominative

This case is used for the subject of the sentence (i.e. the noun doing the verb) and as a complement after: 'bean' ('to be'), 'weortan' ('to become') and 'hatan' ('to be called').

Accusative

This case is used for the direct object (i.e. the noun having the verb done to it/them) and after certain prepositions:

- to (for)

- ijmbe (around)

- geond (through)

- ot (until)

- butan (without)

- wider (contrary to)

- on (against)

- betwix (among)

- tonne (than)

- ofer (during)

- abreotan (failing)

- folgian (following)

- gelice (like)

- minus (minus)

- nahtmidstandan (notwithstanding)

- plus (plus)

- belimpan (regarding)

- geondut (throughout)

- mal (times)

- togänes (towards)

- ungelice (unlike)

- fortonan (because of)

- tonteetan (in order that)

- leesan (in case of)

- interessan (on behalf of)

The accusative case allows for flexible sentence structure that can place emphasis on a certain word by changing its location, yet retaining original meaning. For example:

- Se Hund bit sen Mann - The dog bites the man

- Sen Mann bit se Hund - The dog bites the man

Both of the above Piscean sentences have the same translation into English. On first glance, an English speaker might confuse the second example as 'the man bites the dog', although this is because the object comes before the subject. Because the word 'Mann' is preceded by the accusative article and 'Hund', by the nominative, those skilled in Piscean can easily deduce the sentence's meaning. Meanwhile, the first example places emphasis on the subject, while the second places greater emphasis on the object.

Dative

This case is used for the indirect object (i.e. the noun receiving or being given/sent/lent something); note that in this usage, there is no requirement to translate the word 'to' from English to Piscean:

- Icc geef hit sem Leerere - I give it (to) the teacher

The 'to' is not translated because it is suggested by the dative case ('sem').

When one goes to a place, that place is technically 'receiving' one, so the dative case is used when referring to travel. For example:

- Icc far teem Larenhus - I go to the school; I go to school

Note that proper nouns (that don't take an article) can also be inflected to reflect case:

- Lundenburg - London (nominative)

- Lundenburgen - London (accusative)

- Lundenburgem - London (dative)

- Lundenburges - London (genitive)

- Lundenburgum - London (instrumental)

The action of going to London would involve the dative case:

- Icc far Lundenburgem - I go to London

It is also used after certain prepositions:

- eet (at)

- ut (outside)

- fram (from)

- ofer (about)

- eefter (after/according to)

- ongän (opposite)

- sittan (since)

- butan (except)

- mid (with)

- behionan (alongside)

- rittlingan (astride)

- beforan (before)

- gehende (near)

- escgan (aslant [into])

Genitive

This case is used to denote possession or ownership. 'The man's car' translates literally as 'the car of the man', but without any word for 'of'.

- Teet Äto ses Mann - the man's car (the car of the man)

To put proper nouns into the genitive case: if the noun ends in a consonant, add 'es'; if the nound ends in a vowel or Y, add 's'. For example:

- Teet Rum Seanes - Sean's room (the room of Sean)

- Teet Deejweorc Gaynores - Gaynor's job (the job of Gaynor)

Instrumental

The first use of the instrumental case is to replace words such as 'with' and 'by' in English in the context that they mean 'by means of' - in other words, to indicate that the noun in question is an 'instrument'. Usually, the instrumental case is not used with an article, unless for emphasis; therefore, the noun itself must be inflected. Despite the rule in Piscean that all nouns begin with a capital letter, when in the instrumental case, this capital is dropped. If a noun ends in a consonant, one must add 'um' to make it instrumental; if a noun ends in a vowel, one must add 'num'.

- Teet Bän - the train

- Icc far bänum - I go (by) train

- Teet Culi - the pen

- Icc writ culinum - I write (with a) pen

The second use of the instrumental case is to denote belonging, belief or status. When the noun is inflected, it can become similar to an adjective:

- Englaland - England

- Icc bee englalandum - I am English

- Icc sprec englalandum - I speak English

- Commjunizmäs - communism

- Icc bee commjunizmäsum - I am communist

Irregular prepositions

The third group of prepositions are designated no specific case. They are followed by accusative if they describe where something/things travel or dative if they describe where something/things already is/are. For example:

- Icc far in teen Rum - I go into [the room] (accusative)

- Icc bee in teem Rum - I am in [the room] (dative)

The following prepositions are applied in this manner:

- in (in/into)

- behindan (behind)

- bufan (on top of)

- eetforan (in front of)

- bee (on, e.g. the wall; along)

- oter (next to)

- ofer (over/above; across)

- betweonan (between)

- under (under)

- needrigan (below)

- begeondan (beyond)

- dun (down)

- up (up/upon)

- hinter (past)

- bordan (aboard)

Inflection of various words to reflect case

The above information uses the definite article as a demonstration of inflection to represent case. However, the indefinite article, nouns, adjectives and possessive pronouns can also be inflected.

If there is a definite or indefinite article present, these must be inflected:

- Icc habb teen Culi - I have the pen

- Icc habb anen Culi - I have a pen

- Icc habb anen goden Culi - I have a good pen (note that only the indefinite article is inflected to reflect case; the adjective is inflected to reflect its status as a quasi-modifier; only one part of speech should be inflected to reflect case)

If there are no definite or indefinite articles present, inflect the possessive pronoun (if there is one) and then nothing else:

- Hit brecede meenen Culi - it broke my pen

- Hit brecede meenen goden Culi - it broke my good pen (remember that only one word is inflected to reflect case - here: meenen; inflection of the possessive pronoun is preferable over that of the adjective)

If there are no articles or possessive pronouns present, inflect the adjective (if there is one) and then nothing else:

- Icc habb goden'n Culie - I have good pens

To inflect a quasi-modifier adjective to reflect the accusative case, add '-'n' to it. (This is actually a contraction of '-en' to aid pronunciation; i.e. 'godenen' > 'goden'n'.) The final N is classed as a silent letter, but in spoken Piscean, it indicates that the vocal emphasis should be placed on the last syllable, regardless of where in the word it is usually placed: 'goden = 'GOD-en', whereas 'goden'n' = 'god-EN'. To reflect all other cases, use those endings demonstrated in the 'Lundenburg' example.

Tinte in godenem Culie - ink in good pens ('godenem' reflects dative case, with '-em' suffix)

If there are no other inflectable words available, one must inflect the noun itself. For the accusative case: if the noun ends in '-e', add '-n'n' and if the noun ends in '-en', add '-'n'. For any other case: if the noun ends in a vowel, add '-n-', plus the relevant suffix (see the 'Lundenburg' example); if the noun ends in a consonant, just add the relevant suffix.

Icc habb Informaxionen'n - I have information

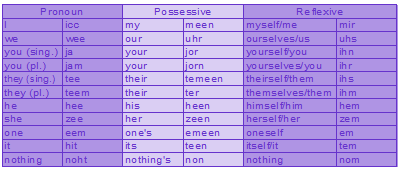

Pronouns

Pronouns in Piscean bear little resemblance to those in either Old English or German. This is because Anderson, Editor of the Piscean Lexicon, deemed their pronouns 'incompatible with the style and rules of the language'. Therefore, a new set of pronouns has been contrived, each with three inflections: pronoun, possessive and reflexive. (Note that, in Piscean, when the reflexive pronoun is referred to, it can be either reflexive or objective: in Piscean, both are the same.)

Below are demonstrations of how the different forms are used:

- Icc bee an Lingwist - I am a linguist (pronoun)

- Meen Boc - My book (possessive pronoun)

- Icc feorme mir - I wash myself (pronoun and reflexive pronoun)

- Frignan naht mir - Don't ask me (reflexive [objective] pronoun)

To say words such as 'mine', 'yours' and 'theirs' in Piscean, find the pronoun that corresponds and use the possessive form of its Piscean equivalent. For example:

- Teet bee meen! - that is mine! (literally, 'that is my!')

- Teet bee jor - that is yours (literally, 'that is your')

Note that the word 'eem' ('one') can be translated either as 'people in general', 'everyone' or 'anyone':

- Eem cunn teet doan - Everyone/anyone can do that

Finally, the word 'noht' ('nothing') can also be translated as 'nobody':

- Noht cunn teet doan - Nothing/nobody can do that

Verbs

Verbs in Piscean are organised into five classes and each, where appropriate, is further conjugated depending on quantity and/or tense.

Infinitive

This is the verb class that one would find in a Piscean dictionary. All verbs end in either '-an' or '-ian' when infinitive.

- bean - to be

- habban - to have

- feormian - to clean

- Feoh - money

- [Feoh habban] bee eem! - [To* have money] is everything!

Observe that an SVO (subject-verb-object) word order is used alongside the infinitive. Money is the subject of the sentence, which comes before the infinitive verb. *The infinitive verb class notably eliminates the need to translate the word 'to' from English to Piscean.

- magan - to like

- plejan - to play

- Compjuter - computer

- Icc mag [compjuterum plejan] - I like [to play on the computer]

The above example demonstrates the use of the infinitive after an auxiliary verb, such as 'magan', which must use a second verb to clarify meaning; in this case, 'plejan'.

Imperative

Imperative verbs express direct commands, requests and prohibitions. The imperative is formed with an infinitive verb in conjunction with the nominative case, a VSO (verb-subject-object) word order and exclamation marks around the sentence (the first of which is only apparent when writing in the Andersonic alphabet).

- macian - to do/to make

- Macian jor Huslarenweorc! - Do your homework! (In Piscean, the exclamation mark is compulsory, while it is optional in English, often used only for emphasis)

- faran - to go

- Faran in Bedd! - Go to bed!

The exclamation marks supposedly indicate the natural intonation that is used for the imperative mood in spoken Piscean.

Indicative

The indicative verb is the most common in the Piscean language, used for factual statements and positive beliefs. It is further split into non-past and past tenses.

Non-past singular

This branch of the Piscean indicative mood is used to refer to events that are actively in progress or that haven't yet happened: either the present or future. The singular form, as opposed to non-past plural, is used for the following pronouns:

- icc (I)

- ja (you [for one person])

- tee (they [for one person])

- hee (he)

- zee (she)

- hit (it)

- ...and after singular nouns

To form the present, one must create a stem from a verb infinitive. For verbs that end in '-an', this ending must be removed, leaving the stem.

- habban - to have

- Icc habb - I have/I am having

For verbs that end in '-ian', this ending must be replaced with '-e'.

- macian - to make

- Icc mace - I make/I am making

- Icc mace Cucen'n - I make cakes (Present uses subject-verb-object word order)

To form the future, follow the noun or pronoun always with 'will' - as an auxiliary verb - and then include the essential verb in its infinitive mood.

- habban - to have

- Icc will habban - I will have/I will be having

- Icc will Eefenwisten habban - I will have dinner (Future uses subject-(aux verb)-object-verb word order)

Non-past plural

This used for the same purpose as the non-past singular, but applies to only the following pronouns:

- wee (we)

- jam (you [for more than one person])

- teem (they [for more than one person])

- eem (one)

- noht (nothing)

- ...and after plural nouns

To form the present, one must create a stem as in the instructions for the non-past singular. If the stem ends in a consonant, add '-en' to alter it to the non-past plural. If the stem ends in '-e', simply add '-n'.

- habban - to have

- Wee habben - we have/we are having

- Wee habben Eefenwisten - we have dinner

Form the future using 'willen' after the noun or pronoun along with the essential verb in its infinitive form.

- Wee willen habban - we will have/we will be having

- Wee willen Eefenwisten habban - we will have dinner

Past singular

The same rules as the nonpast singular apply, except for one additional step. If the stem ends in a consonant, add '-ede'; if the stem ends in '-e', add '-de'.

- Icc habb - I have

- Icc habbede - I had/I have had

- Icc bee - I am

- Icc beede - I was/I have been

- Icc writ - I write

- Icc writede - I wrote/I have written

- Icc writede anen Boc - I wrote a book/I have written a book

Past plural

The same rules as the past singular apply, but '-n' must be added.

- Icc habbede - I had/I have had (singular)

- Wee habbeden - we had/we have had (plural)

- Wee beeden

- Wee writeden

Interrogative

Verbs in inflected in this manner if they are used to ask questions. The interrogative mood not normally issued with a pronoun, but if context does not make the addressee clear, a pronoun - or, indeed, noun - can be included after the interrogative verb.

Non-past

For the present: firstly, create a stem according to aforementioned instructions. If it ends in a consonant, add '-est' to make it interrogative; if it ends in '-e', add '-st'.

- Habbest? - do you have/are you having?

- Writest? - do you write/are you writing?

- Macest? - do you make/are you making?

- Habbest anen Culi? - do you have a pen? (Interrogative present uses verb-subject-object word order)

For the future, always use the interrogative verb 'willest', with the essential verb in infinitive form inverted to the end of the sentence.

- Willest habban? - will you have/will you be having?

- Willest writan? - will you write/will you be writing?

- Willest macian? - will you make/will you be making?

- Willest anen Culi habban? - will you have a pen? (Interrogative future uses (aux verb)-subject-object-verb word order)

Past

To form the interrogative past, inflect the verb as in the indicative past singular, then add '-st'.

- Habbedest? - did you have/were you having?

- Writedest? - did you write/were you writing?

- Macedest? - did you make/were you making?

- Habbedest anen Culi? - did you have a pen?

Using the interrogative mood with nouns and pronouns, etc

Begin the sentence with the interrogative, non-past or past, verb and follow it with the subject, then a comma, then the rest of the sentence.

- Onbrejdest teet Geschäft, ta? - does the shop open, when? (When does the shop open?)

- Onbrejdedest teet Geschäft, ta? - did the shop open, when? (When did the shop open?)

Conditional

The conditional mood is used to speak of an event whose realisation is dependent on a certain condition.

Non-past

First create a stem, as one would in the indicative present singular mood and then subject the first vowel in the stem to a vowel shift. Vowel shifts occur in a predefined manner, with one vowel mapping to another (refer to the section 'Vowel shifts').

- Icc bee an Lingwist - I am a linguist (indicative)

- Icc bo an Lingwist - I would be a linguist (conditional - 'bee' has been subjected to a vowel shift, rendering it 'bo')

- Se Hund bit - the dog bites/the dog is biting (indicative)

- Se Hund bijt - the dog would bite (conditional)

Note that when one puts 'cunn' ('can') into the conditional non-past mood, it changes its meaning to 'could'. Because this is an auxiliary verb, one must invert the essential verb, in its infinitive form, to the end of the sentence.

- Se Hund cenn bitan - the dog could bite

- Icc cenn an Lingwist bean - I could be a linguist

If a situation requires a conditional verb to be inverted to the end of a sentence, it can be made into a quasi-infinitive. Add '-an' onto the end of the conditional stem.

- Ta ja naht cut wikium boan - if you are not familiar with Wikis (when 'bo' becomes a quasi-infinitive, it is 'boan')

Past

To form the conditional past: firstly, follow the instructions for the conditional non-past to retrieve a conditional stem. If this stem ends in a vowel, add '-de'; if it ends in a consonant, add '-ede'.

- Icc bode an Lingwist - I would have been a linguist

- Se Hund bijtede - the dog would have bitten

'Cunn' ('can'), when put into the conditional past, means 'could have'.

- Se Hund cennede bitan - the dog could have bitten

- Icc cennede an Lingwist bean - I could have been a linguist

'If' and 'when'

The English words 'if' and 'when' are both translated as 'ta'. Usage of the indicative mood defines 'ta' as 'when', while usage of the conditional mood defines 'ta' as 'if'.

- Ta icc far - when I go (indicative)

- Ta icc fär - if I go (conditional)

Jussive

The jussive mood in Piscean is used to express plea, insistence, imploring, self-encouragement, wish and desire.

Non-past

One must use the conditional form of 'will' ('wijl') and the quasi-infinitive conditional form of the essential verb (subjected to vowel shift).

- Se Hund wijl bijtan - the dog should bite

- Icc wijl an Lingwist boan - I should be a linguist

Past

The jussive past is formed in a similar manner to the jussive non-past, but substituting the conditional past form of the essential verb for the quasi-infinitive form (subjected to vowel shift).

- Se Hund wijl bijtede - the dog should have bitten

- Icc wijl an Lingwist bode - I should have been a linguist

Dubitative

The dubitative mood expresses the speaker's doubt, uncertainty or speculation about the event denoted by the verb.

Presumptive non-past

This form of the dubitative indicates a presumption or possible event.

- Hee bee in Californjenem - He is in California (indicative)

- Hee beedog in Californjenem - He might be in California

The suffix '-dog' is attached to the non-past singular form of verb.

Presumptive past

The presumptive past is the same as the presumptive non-past except that the suffix '-dog' is attached to the past singular form of verb.

- Hee beededog in Californjenem - He might have been in California

Assumptive non-past

This form of the dubitative indicates an assumption or - at least what the speaker believes to be - a probable event.

- Beedog hee in Californjenem - He must be in California

It is similar to the presumptive, but requires a shift of syntax. While the presumptive requires SVO, the assumptive requires VSO, thus placing greater emphasis on the verb.

Assumptive past

This is similar to the assumptive non-past, but the suffix '-dog' must be attached to the past singular form of a verb.

- Beededog hee in Californjenem - He must have been in California

Vowel shifts

Verbs in both the conditional and jussive moods undergo predetermined vowel shifts. In some cases, single vowels substitute for double ones (the vowel is 'strengthened').

- a > ä, any double consonants that follow change to single consonant

e.g. 'habb' > 'häb'

- e OR ee > o

e.g. 'bee' > 'bo'

- i > ij, any double consonants that follow change to single consonant

e.g. 'bit' > 'bijt'

- o > u

e.g. 'do' > 'du'

- u > e

e.g. 'cunn' > 'cenn

- ij > a

e.g. 'hijd' > 'had'

Even though IJ is not considered a vowel in its own right, but a dipthong, the two letters collapse into A.

- eo > ue

e.g. 'weorc' > 'wuerc'

Not a vowel, but with the vowel shift, the letters are easier to pronounce than what they should be.

- ä > eo

e.g. 'bät' > 'beot'

Voice

Piscean has two voices for verbs: the active and the passive. The active form follows the basic SVO pattern, whereas the passive voice is derived by a shift of syntax, while retaining relevant cases. Observe

- Icc see Bill - I see Bill

- Bill see icc - Bill is seen by me

- Bill see mir - Bill sees me

- Mir see Bill - I am seen by Bill

- Se Hund bit sen Mann - the dog bites the man

- Sen Mann bit se Hund - the man is bitten by the dog

- Se Mann bit sen Hund - the man bites the dog

- Sen Hund bit se Mann - the dog is bitten by the man

The English 'third voice' can also be translated using an artificial pronoun - 'jo' - (and the SVO word order) in Piscean.

- Jo schnijd hänlic teen Bräd - the bread slices poorly (note that the bread itself is not slicing, but the phrase expresses that it can't be sliced easily)

- Jo ciep god heen Romane - his novels sell well

'Bean' and 'zijan'

The Piscean language has a loan feature from Spanish: two verbs that can both be translated into English as 'to be'.

The first of these, 'bean', describes the condition of something. Observe:

- Teet Eepel bee grene - the apple is green (because it is unripe)

This example speaks of the apple's condition. The apple is green, as it has not yet ripened. When the condition of the apple changes, it will no longer be green - it will be ripe.

The second of the verbs, 'zijan', describes the essential characteristics of something. Observe:

- Teet Eepel zij grene - the apple is green (by nature)

In this case, the apple is green in colour and remains green even after it has ripened.

Overall, 'bean' tells one how something is, whereas 'zijan' tells us what feature something has.

- Icc bee mete - I am currently tired

- Icc zij mete - I am generally tired

- Icc bee feegen - I am currently happy

- Icc zij feegen - I am generally happy

- Zee bee ruhij - she's being quiet

- Zee zij ruhij - she is introverted

- Icc bee fus - I am ready

- Icc zij fus - I'm ready for anything/I'm a quick thinker

Note that when an irreversible change has occurred, 'bean' is still used.

- Hee bee däd - he is (currently) dead

- Teet Äto bee abreotede - the car is (currently) destroyed

While this instruction may seem to contradict previous rules, it has a reason: in the examples, the person cannot be 'generally dead' and the car can't be 'generally destroyed'. The objects are not necessarily supposed to be that way and, as such, the adjectives describe their conditions.

Note that in these situations, 'zijan' is still sometimes used for idioms. For example:

- Hee zij däd - he is a dull and unresponsive person

- Teet Äto zij abreotede - the car is falling to pieces

Adjectives and adverbs

Adjectives in Piscean exist in two forms. The first is the sole stem of the adjective, forming a statement. In this case, the adjective always comes after the noun.

- Teet Culi bee god - the pen is good

- Teet Äto bee niwe - the car is new

This form of adjective, when preceding or following a verb other than 'bean', also serves as an adverb.

- Se Mann beede god gearcede - the man was well prepared

The second occurs when the adjective modifies the noun. If this is the case, the adjective comes directly before the noun and is altered.

- Teet goden Culi - the good pen

- Teet niwen Äto - the new car

To alter a modifying adjective that ends in an E, suffix '-n'. For one that ends in any other letter, add '-en'.

Nouns

All nouns are capitalised in Piscean, clearly showing their function within a sentence.

Like most Germanic languages, Piscean forms left-branching noun compounds, where the first noun modifies the category given by the second. For example: Hundenhutte (dog hut or doghouse). Unlike English, where newer compounds or combinations of longer nouns are often written in open form with separating spaces, Piscean always uses the closed form without spaces. For example: Treowenhus (tree house).

Piscean compounds also assist in the differentiation of a compound adjective from two adjacent adjectives that each independently modify the noun. Compare the following examples:

- Essijzoweren Zojrenlauzung - acid solution that is acetic > acetic acid solution

- Essijzoweren Zojre Lauzung - solution of acetic acid > acetic-acid solution

- Runden Beod Reedung - discussion held at the round table > round-table discussion

- Runden Beodenreedung - table discussion that is round > round table discussion (note that this does not make sense)